At Leisure

AT LEISURE | What Keeps India's Former RAW Chief Awake At Night?

Anmol N Jain, Diksha Yadav, and Prakhar Gupta

Jan 25, 2026, 06:00 AM | Updated Jan 26, 2026, 04:18 PM IST

The video call connects, and Vikram Sood's face fills the screen. Behind him: a ceiling fan, some paintings on white walls. The interior of his home has no secret lairs, no walls of monitors, no maps with pins in them. Just an 82-year-old man in a pale blue shirt, speaking from what appears to be his living room.

This is what a former chief of the Research and Analysis Wing looks like in retirement. Not James Bond. Not even George Smiley. "James Bond is fantasy," Sood has said elsewhere. On Bollywood spy thrillers like Pathaan and Ek Tha Tiger, he is blunt: "Hilarious." And on the romantic plotlines where RAW and ISI agents fall in love? "He'll be shot if he does that."

Sood led India's external intelligence agency from December 2000 to March 2003, serving under Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee during some of the most fraught years in recent memory: the aftermath of Kargil, the Parliament attack, the post-9/11 realignment. Before that, he spent 31 years in the agency, having joined in 1972 after a stint in the Indian Postal Service.

His path to espionage was unconventional. Economics at St. Stephen's College, then a civil services posting sorting mail, then an interview with 'someone' from the upper echelons of RAW. The rest too is classified.

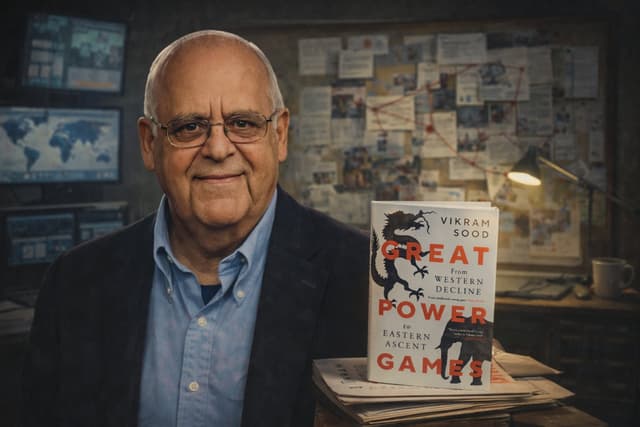

Now 22 years out of service, Sood has found a second career as a writer and commentator. His latest book, Great Power Games: From Western Decline to Eastern Ascent, released in October 2025, completes a trilogy that began with The Unending Game (2018) and continued with The Ultimate Goal (2020). The progression tracks his intellectual preoccupations: from the mechanics of espionage, to narrative warfare, to the shifting tectonic plates of global power.

Three of us from Swarajya—Diksha Yadav, Prakhar Gupta, and I—spoke to him on 16 January. This was a week after he addressed the Mangaluru Lit Fest, where he called Pakistan "a banana republic with a nuclear bomb" and criticised the United States for "creating problems across the world."

A few days earlier, American special forces captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro in a predawn raid and flew him to New York. Two weeks before that, protests erupted across Iran. The world, as one of us remarked at the start of the call, feels unusually chaotic.

Sood's response was matter-of-fact. "I never imagined it would be this chaotic," he said. Then he paused, as if reconsidering.

His central thesis is stark, and he states it early. "Wars are profitable," he says. "Peace? No, no." A pause. "Ill health is profitable. Good health is not."

This is how Sood speaks: flat delivery, devastating implications. He talks like a man accustomed to briefing people who do not have time for equivocation.

"The West grew in a corporate fashion," he explains. "It was the corporates: the Rockefellers, the Carnegies, J.P. Morgan, who led America into becoming a big power. Henry Ford and others came later. That's how they developed. The Soviet model was the state. We were caught midway, neither here nor there, therefore we stagnated." He allows himself a small smile. "Couldn't make up our mind whether we wanted to be a mixed economy. Became a mixed-up economy."

And China? "The West went to China thinking that once they get rich and powerful, they'll become democratic automatically. Actually, they were looking for cheaper products from a country where restrictions on wages and hours of work would not apply. Slave labour to bring cheaper products into the rest of the world." The result, as he puts it: "The Americans became just a software country, social welfare and non-manufacturing. And the Chinese took over the manufacturing."

His main theme, he says, is simple: "If you don't manufacture in your own country, you can't become truly powerful."

But manufacturing narratives is an equally important road to power. The Iraq War is his touchstone. Soon after 9/11, Donald Rumsfeld wanted intelligence on Iraq, not Al-Qaeda. "Give me the dope on Iraq," Sood paraphrases. "Sweep it all in." Never mind that Saddam Hussein had nothing to do with the attacks. A narrative was needed: weapons of mass destruction, sheltering terrorists. "Both were not true. But the story is sold."

The real objective? Saddam had switched from pricing oil in dollars to euros. "By May, that had been corrected. George Bush went on board the ship and said 'mission accomplished.' Three months after they had attacked." The rest, he says, is history.

When we raise the Russia-Ukraine war, Sood does not explain. He interrogates. Throughout our conversation, he poses questions instead of making statements, a habit that feels distinctly like professional training.

"Has Ukraine been accepted in NATO?" No. "Has Ukraine pushed back the Russians?" No. "Has NATO been able to do anything?" No. "Have the Europeans put in their soldiers?" No. "Has Russia gained territory?" Yes. "Have they been able to withstand the pressures on them?" Yes.

"So you balance it out and you know that the Russians have won. It's only a matter of time and declaration."

Who benefits from the prolonged conflict? "Who sells the weapons to the Ukrainians? Who uses them? And who replenishes them? Three simple questions. If you can answer them, then you know the answer."

The answer, of course, is the United States. But Sood is careful to distinguish between the American people and what he calls "the Wall Street State Department": a nexus of defence contractors, think tanks, and congressional interests that shapes policy beyond any elected official. This is the "deep state" he references throughout Great Power Games, though he uses the term without the conspiratorial overtones it has acquired elsewhere. For him, it is simply a description of how power actually operates.

He notes that William Burns, then US ambassador in Moscow and later CIA director, warned his own government: Ukraine is a nyet-nyet. Don't do it. "But when you are riding high, you think this will be the end of Russia. You go ahead and try it out and see what happens. How many thousands of people have died? And they are all non-American, and the interest is American."

Prakhar pivots to Iran. Massive protests have erupted, with talk of regime change. India's past experience of the Shah regime, which supported Pakistan, was far from positive. Would India prefer a US-aligned Shah or the sanctioned mullahs?

"I'm not too sure they will be able to get the Pahlavis in so easily," Sood replies. "The match is not over yet."

But if pressed?

"India's preference will hardly matter. It's Hobson's choice. We'll have to deal with whoever is in power. The Americans only pursue their national interest, and these days their national interests are imperial."

As for Bangladesh, Sood believes Sheikh Hasina lost control. Nepotism, favouring her own system. But he adds historical context most would miss: "Don't forget that the original name of the Awami League of Sheikh Mujib was called the Muslim Awami League. Their first riot against Pakistan was when they wanted to declare Urdu as the national language. It's after that he changed the name of his party, became secular." He pauses. "Who knows if Bhutto had allowed Sheikh Mujib to become Prime Minister after the 1970 elections. History might have been different."

On whether India missed the warning signs, he demurs: "I wouldn't know what happened behind the scenes."

But on the nature of such upheavals, he is categorical. "Riots and movements are not spontaneous. They are created. There has to be a totem pole. There has to be people around it. There has to be organisation. There has to be funds. And a plan laid out."

We turn to Venezuela. Trump declared the US would "run" the country until a transition government forms.

"Some people call it the Donroe Doctrine," Sood says, "instead of the Monroe Doctrine." The portmanteau had been coined by the New York Post and embraced by the administration.

"Some people say it's a very smart move. It knocks out China from the region. When you also say you're going to take Greenland, you get the two together." He pauses. "Acting in imperial interests is the right thing to do. But it is against all rules that they themselves have laid out for us. Do you think we could do this anywhere in our neighbourhood? We don't have that power. They do."

Diksha observes that nobody even pretends to be the good guy anymore.

"Just to add to that," I interject, "the US used to call itself the 'benevolent hegemon.' But now, if you look at the new National Security Strategy, they're blatant about what they want. In Venezuela, there's not even an ounce of pretence. So, have narratives stopped mattering?"

Sood considers this. The shift in American posture seems to interest him.

"I do think these days they're in a state where they say 'I don't care. I'll do what I want to do.' Previously they went to great lengths to pretend to be peacemakers and restorers of democracies, battling against communism for the good of the world. Now all that is over. You're quite right. Now the narrative is," he adopts a mock-swagger, "I am the local dada. I'll do what I like to do. I've taken over Venezuela. What can you do to me?"

And the world's response? "Nobody is asking him to back off. China has said nothing. Russia has said nothing. We've said it's 'unfortunate.' After Ukraine, after Hamas, people have stopped saying 'get off now.'"

Then he ventures a speculation: some believe it's all to distract from the Epstein files. "Clinton kept the world busy with his Balkan wars in the 90s. We know why." He shrugs. "We don't know whether Mr Trump has a grand plan that will get him the Peace Prize. He's already got it secondhand. That lady handed over her prize to him and he took it."

Midway through this exchange, his doorbell rings. Sood excuses himself. "Just leave them there and I'll bring them home," we hear him say to someone off-screen. He returns without comment, picking up exactly where he left off. Even former spy chiefs have parcels to collect.

"Narratives don't have to be truthful," he says, returning to his central theme. "They have to be perceived to be true. It is how you are made to receive them."

If Sood is unsparing about American imperialism, he is equally critical of India's failures in this domain.

"Look at the amount of wealth and possibilities the West has to create narratives. And they have had a head start. In 1962, we didn't even have TV here. The West was controlling all the waves: theatre, painting, music, politics, sports. Everything about the West was wonderful. And the countries behind the Iron Curtain? Hungry, foodless, standing in queues, wearing old-fashioned clothes. That was the depiction. And we accepted all that."

The BBC's refusal to call terrorists "terrorists" after 26/11 still rankles. "They didn't even use the word 'Pakistani.' Just 'gunman.'" More recently, the UK grooming gangs scandal: "They are Pakistanis mostly, but now they call them 'South Asian.' One word you change and you change the context."

Anmol brings up Hollywood. In his book, he describes how Chinese executives met with studio heads. "And from then on, Hollywood movies were specific about how they portrayed China: not as an adversary, but as a partner that had to be respected. India, being a democracy, can't control cinema the same way. Does narrative warfare come down to what kind of government you have?"

"You know, USA is a democracy by all yardsticks," Sood replies. "But they had CIA and Pentagon liaison officers in Hollywood. They would tell them what to make, what not to make, how to make the film, which portions to take out." He lets that land. "So it's a democracy doing this. And the same studios, because they want money from China, were told to cut certain portions. They happily did. China is money bags for them."

Can India do the same?

"Even if you are powerful enough to tell them: 'no more Hollywood films in India,' half of our Western-loving population will go to war on us. The Chinese never say anything when their government acts. Here, it will be: 'Because they're telling the truth, you're banning them!'"

He notes India's global reach deficit: "How many TV stations in the rest of the world have Indian channels? Who do we have in America? So how will the narrative be spread?"

His prescription: Indian cinema. "Bollywood is a big, big possibility. Southern cinema too. They have to be brought into thinking that it's not so bad to talk about Indian values, Indian systems. And I don't mind if there is criticism also. That helps. You have the capacity to make satire about Indian politicians, please do."

Has he seen Dhurandhar, the RAW thriller that broke box office records?

"No, I haven't got to Dhurandhar yet." He explains, matter-of-factly: "Where we live and where the cinema halls are, it takes an hour and a half to get there. Three and a half hours of the movie. Hour and a half to get back." He plans to wait for Netflix. "Then you can switch off when you want to go to bed or have dinner, and watch it again."

But he has heard good things. "I believe it's one of the best movies ever, especially in this field. It resonates with the common man. It's about your own country being put to trouble by terrorists. It gives you a reason to hang together, and not be driven by false senses of differences."

It is a small detail, but telling. An 82-year-old retired spy chief, interested in a film about his former profession, waiting for the streaming release because the theatre is too far and the runtime too long. The logistics of age.

Anmol picks up from his comment about Dhurandhar. "Talking about Dhurandhar, we saw a lot of opposition and people getting hurt within the country over what the movie showed. I don't think Pakistanis were as unhappy as some people in our own country. You talk about a 'clash of civilisations' in your book, and we've heard this idea of a 0.5 front within the country, a threat as potent as the two external fronts we face. Can we say this clash is not just about the international theatre? Is it unfolding within the country too?"

"Leading question," he says immediately. It is the closest he comes to a deflection in all conversation. "Difficult for me to answer."

But he does answer, carefully. "They used to ask me: 'You've got so many Muslims in your country, how do you handle them?' I said, 'because they were born there, we know them.'" He contrasts this with Europe. "You have imported them. They are alien to your culture. For us, they are not alien. They look like us, they eat like us, they wear clothes like us, they speak like us."

Are there problems? "Of course there are pockets where we get into trouble. We've had riots in the past. We had them in Delhi not so long ago. This is the reality of India."

But we sense he does not want to dwell on this and move on to global order. "Trump talked about G2 early in his presidency. Now there's talk of Core Five. With American overstretch, what kind of grouping can actually provide stability?"

"Did you read my last chapter carefully?" He smiles. "The last para. Maybe the three leaders, Russian, Indian, and Chinese, assisted by their able foreign ministers and national security advisors, need to sit down together and look at the changing world. To find some new roads to permanent peace."

RIC Troika?

He invokes Palmerston, who had in 1848 stated that Britain has "no eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies." Clearly referring to China, Sood says, "at least we can say we have no permanent enemies."

He then paints a geographic vision. "Look at the map. Arctic Ocean, Russia, China, India. Take a train from Trivandrum to Vladivostok. Take a ship from Vishakhapatnam into the Arctic Ocean. The trade patterns will change if the Arctic becomes commercially navigable. We have 1.4 billion here, 1.3 billion there. We have enough gas and oil in Russia. We don't covet Russian land. They don't covet Indian land."

He pauses. "China, we have problems with. That has to be solved. Pakistan is unsolvable in my mind."

"Also insolvent," I add.

Sood chuckles. "Peace with Pakistan is not possible. Asim Munir will say: 'We are Muslims, we are Jihadis. We will do Jihad.' That is your army chief saying this. He's telling his own soldiers they are jihadis. 'Hindu and Muslim, they do not live together.' This is what is in his mind."

The structural problem, as Sood sees it, is that the Pakistan Army needs India as an enemy to justify its outsized role. "If Pakistan does not have India as an enemy, then what is the relevance of the Pakistan Army being so strong? They have no viable excuse or reason." He recalls how Prime Minister Modi turned up for Nawaz Sharif's grandchild's wedding. "The Pakistan Army was most upset. I think they threw him out for the time being and then brought him back again."

Hence his formulation: "Pakistan belongs to the Pakistan Army, not the other way around."

Can it be solved?

"You have to manage. You can't change geography, you can't change history. But you can manage the future."

Managing, when provoked, means responding. We circle to Operation Sindoor, India's military response to the Pahalgam attack in May 2025. The strikes were successful. The communications were not.

"We did everything right. We did a marvellous job. Who should have been out first with the news? First, alongside. Not waiting for them to say anything." Instead, India allowed Pakistan to shape the initial narrative. "Otherwise it becomes a reaction. The guy who hits first, you're then looking for an equaliser. They should have put it out straight away: 'We've knocked off eleven of their sites. They're suing for peace. Done. Finished. Donald Trump can say what he likes.'"

Prakhar notes that during Kargil, India released intercepts of Musharraf speaking to his generals. We managed the information war better then.

"Kargil was a long-drawn affair," Sood responds. "There was no social media then. News came in slowly. Here, before the operation is over, you have ten people on TV giving ten different versions, all claiming authoritative sources."

Can social media be controlled?

"Very difficult, short of shutting it down. And that's a bad scene." He recalls IC-814, the 1999 hijacking. "There was so much tamasha on the streets of Delhi. The masses pressured the government into acting sooner than they should have."

"It has to be done by you guys," he says, looking at us directly. "You are the information and opinion makers. Governments will give you accurate statements, not aggressive enough. But it is us who have to do it ourselves."

I pick up a thread he had raised earlier: that citizens, not just governments, must carry the narrative. "Yes. During Operation Sindoor, we saw that the most unlikely section, the fans of K-pop, fans of BTS, actually pushed back on TikTok against the narratives being spread by Pakistanis and Chinese."

This leads to the obvious question. "As the former head of RAW—" Anmol catches himself. "Sorry, R&AW."

Sood chuckles appreciatively at the correction.

"What keeps you awake at night in 2026 with everything that is happening in the world?"

"What keeps me awake?" He pauses. "Actually, nothing does."

"But as a phrase," he continues, "what worries me most is unemployed youth."

It is not the answer we expected. Not China, not Pakistan, not terrorism, not narrative warfare.

"That will be a crisis. Which will lead to other crises. Regional clashes, language clashes, caste. You already see some signs: ki bahar ka koi aap ke yaha kyun hai, why is someone from 'outside' working here?"

He sees it in his own household. "People who work with us, for us. The great desire to educate the child and make him better than they were. That has to be encouraged."

It is not just mega projects, he says. "It will be the small projects, in huge numbers. Because everybody is not going to be a millionaire. But everybody must have something to do, to take money home, to educate the children."

Whose responsibility? "It is not the government's sole responsibility to find jobs. It is the corporate world which must find the jobs, and the government must make it easy for them. Not too many rules, not too many restrictions."

He returns to Bangladesh. "They created the mess and the students came out in the streets."

Diksha notes that the playbook was labelled "Gen Z protest" and exported to Nepal. They were expecting India to follow.

"Each politician now makes it a point to mention Gen Z," we observe.

He laughs. "I don't know, I guess we are lucky we don't have that situation. But doesn't mean it won't happen." His characteristic questioning to make a point kicks in: "Do you think the CAA protests and the Farm Bill protests were spontaneous?"

"Clearly not," Anmol replies almost instantly.

"And those guys who came from the Grand Trunk Road, from Ludhiana or Jalandhar, in their Mercedes and vans and air conditioners and dishwashers, had their kebabs." He lets the image settle. "Was that a farmer protesting? Poor guy, he doesn't have that luxury. A lot of money had gone into this. A lot of direction."

He pauses. "It could have gone the other way. There could have been a violent turn. It was bad enough, but still, I think the government acted with great restraint. At the time, it was criticised."

A beat. "We are not an easy country to govern."

He knows. He has seen it up close.

"Now we have vote-chori and EVMs, our elections being discredited," says Anmol.

Sood chuckles. "You don't discredit if you win that election. But you discredit if you lose the election."

"But that is dangerous for democracy in the long run," we push back. "If institutions are discredited and you don't accept any of the outcomes."

"That is the second big fear," he says, serious now. "If you start discrediting your systems, then where do you go? Then you're going to take the law into your own hands."

Towards the end, Sood is reflecting on how little individuals matter in the grand sweep of geopolitics. "We don't matter," he says. "In the long run, we don't matter to national vested interests. We're just a number."

The Americans bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki when Japan was about to concede defeat, he reminds us. "A quarter million people died in six seconds. What was the idea? To send a message to the Russians post-war. That 'we are the big guys on the scene.' So how do we matter in this ultimate analysis?"

"That's how you start your book," Anmol recollects. "Quoting Carl Sagan. That we are just a pale blue dot."

Sood smiles and picks it up. "I do, and we fight tooth and nail over it." He pauses. "A little bit of humility helps, no? Not too much. Little bit is okay. Don't be subservient."

It is a curious note from a man who has spent an hour diagnosing great power machinations, narrative warfare, imperial overstretch, and civilisational competition. But perhaps that is the point. The pale blue dot is worth fighting for. Just not so hard that you forget what you are fighting for.

"So you've got to get your act together, boys and girls," he had said earlier, addressing us directly. The stakes are real. More will happen in our lifetimes than in his remaining years.

Diksha thanks him and recommends the book to our viewers. Sood smiles.

"Thank you. I enjoyed myself."

Anmol N Jain (@teanmol) is a writer and lawyer with a background in International Relations, Political Science, and Economics. Diksha Yadav (@dikshayadav_) is a senior sub-editor at Swarajya. Prakhar Gupta (@prakharkgupta) is a senior editor at Swarajya.