Heritage

Harappans Did Not Vanish. New Science Shows How They Evolved When The Rivers Ran Dry

Aravindan Neelakandan

Dec 07, 2025, 07:00 AM | Updated Dec 06, 2025, 01:01 PM IST

For close to a century since the announcement of its discovery in 1924, the 'collapse' of the Indus Valley Civilisation remained one of archaeology's most profound puzzles.

Mystery of a 'Vanished' Civilisation

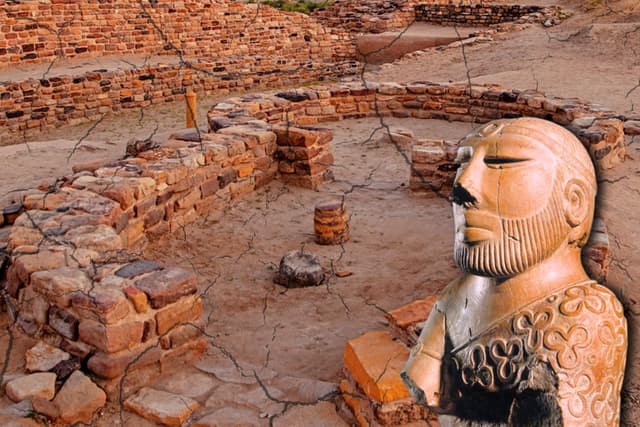

Majestic cities like Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro, which had flourished for over a thousand years with sophisticated urban planning, advanced drainage systems, and intricate trade networks spanning thousands of kilometres, seemingly vanished around 3,900 years ago.

Colonial wisdom blamed external invaders – the 'Aryan invasion' theory persisted through much of the twentieth century, a narrative that shaped how generations understood the ancient Indian history. But scientific evidence accumulated over the recent decade has fundamentally transformed this narrative.

The shift reveals something profound about how science itself progresses: not through sudden revelations or revolutionary paradigm shifts, but through incremental refinements of data and methodology that build systematically upon earlier discoveries.

New Researches and New Paradigms

This transformation is exemplified in two research papers published on the subject within ten years.

In 2018 researchers from the Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, and the Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology published findings from Tso Moriri Lake in Ladakh. They presented compelling evidence of a prolonged drought lasting roughly 900 years, beginning around 4,350 years ago, driven by a weakening Indian summer monsoon that reduced precipitation across northwest India and the Himalayan regions.

This research provided a crucial climate foundation for understanding urban decline and population dispersal – a scientific basis for the transformation rather than conquest or a sudden catastrophic demise.

But the study was geographically limited – coming from high-altitude lake sediments in the remote Himalayas, far from the heartland where Harappan populations concentrated along the Indus River and its tributaries.

The data pointed to climate stress as a contributing factor in civilisation's transformation, yet significant questions remained unanswered: How severe were these droughts in the populated regions themselves? How spatially extensive did they spread across the civilisation's domain? And crucially, how did river systems themselves respond to these climatic shifts?

2025: IIT Gandhinagar Study

In 2025, a new study by Solanki et al published in Communications Earth & Environment answers precisely these questions through an unprecedented integration of climate modelling, hydrological simulation, and paleoclimate evidence.

The research, conducted by teams at the Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar and international collaborators from the University of Arizona and University of Colorado Boulder, reveals not simply a single prolonged drought, but four distinct, severe drought events spanning approximately 1,000 years, each lasting decades to centuries.

More significantly, the study quantifies river discharge reductions across the Indus basin with regional precision unprecedented in paleoclimate research, demonstrating how climatic stress cascaded through the river systems that underpinned Harappan agriculture and civilisation.

This newer work validates, extends, and substantially refines the 2018 findings, with data-driven precision that exemplifies how scientific understanding actually progresses over time.

The new study employs three transient climate simulations (TraCE-21ka, MPI, and TR6AV) – computational models spanning 22,000 to 6,000 years of Earth's climate evolution – to reconstruct meteorological conditions across the Harappan period with delicate resolution and temporal precision.

These simulations force the Variable Infiltration Capacity (VIC) hydrological model, a sophisticated tool that converts rainfall and temperature data into streamflow estimates at high spatial resolution over the entire region.

The technique transforms abstract climate variables into the tangible, agriculturally relevant metric: river discharge measured in cubic metres per second, the actual water available for irrigation agriculture.

Model calibration against modern observed discharge data from 1813 to 2006 demonstrates skill across major Indian river basins, providing confidence in paleo-discharge reconstructions for periods lacking instrumental data. This represents a significant advance over purely proxy-based approaches.

The Discoveries

The results are striking in their precision and specificity. Between approximately 4,400 and 3,400 years before present, four major drought events unfolded with measurable consequences for human populations.

The first, around 4,445-4,358 years BP, affected approximately 65% of the Indus Valley Civilisation region with roughly 5% rainfall reduction compared to earlier Pre-Harappan conditions.

The second, coinciding with the so-called "4200-year event" (4122-4021 years BP), proved more severe, particularly in central regions spanning from modern Punjab through Sindh where major urban centres concentrated.

The third drought (3826-3663 years BP), peaking at 3,757 years BP, emerges as the most devastating – lasting 164 years, reducing annual rainfall by approximately 13%, and affecting 91% of the IVC region in what researchers term the most severe event by combined measures of duration, intensity, and areal extent.

The fourth event (3531-3418 years BP) delivered prolonged summer and winter drought simultaneously, with some locations experiencing discharge reductions exceeding 12 percentage.

This temporal precision matters profoundly for understanding societal response and adaptive strategies. Populations don't merely respond to average conditions; they respond to crisis sequences and their psychological impacts over extended timescales.

A 164-year drought, particularly one arriving after three preceding episodes totalling several centuries of hydroclimatic instability, presents an entirely different adaptive challenge than abstract 900-year averages suggest.

Institutional memory frays; agricultural knowledge systems adapted to different rainfall patterns become unreliable; social structures calibrated for resource predictability strain under persistent stress. The psychological and social toll of century-scale uncertainty cannot be underestimated in understanding how societies fragment and reorganise under environmental pressure.

The Role of Ghaggar-Hakra Paleo-Channel

Critically, the new discharge data illuminates why the Ghaggar-Hakra declined differentially from other basin systems.

Particularly, during the first two droughts, stronger winter monsoon rainfall, especially across the Ghaggar–Hakra interfluve helped the Harappans to ease out the drought. However, once winter monsoon precipitation also declined after ~3300 BP, Harappan settlements fragmented into smaller.

The Ghaggar-Hakra lacks the glacial-fed component that provides stability to the main Indus system during monsoon failures. When monsoon rains weakened – the primary water source for the Ghaggar-Hakra – the system experienced flow reductions which severely affected the lives of Harappan people. (Is this why Saraswati was praised as the best of the mothers?)

The most severe drought event (D3), lasting 164 years and peaking at 3,757 years BP, produced discharge reductions also in Ghaggar-Hakra stations. This threshold proved critical: archaeological evidence shows widespread abandonment of settlements in the central Ghaggar-Hakra region during the Late Harappan period, precisely coinciding with this interval.

Thus the new study solves one aspect of the Saraswati mystery: it demonstrates quantitatively why settlements abandoned the Ghaggar-Hakra paleochannel during specific intervals. But the deeper puzzle remains – was this system an independent riverine entity, as some geological evidence suggests, or a tributary component of a larger paleochannel network?

Either way Saraswati played an important role for the Indus-Sarasvati people.

Continuity Through Transformation

Critically, the 2025 study rejects the narrative of sudden collapse entirely and supports instead a complex, protracted transformation spanning centuries – a position strongly resonating with archaeological evidence and compatible with the adaptive resilience.

The research demonstrates regional heterogeneity in climate stress across the civilisation's domain. Saurashtra experienced relatively modest discharge reductions and maintained favourable rainfall patterns through Late Harappan times.

Archaeological evidence shows sustained Late Harappan occupations in this region – settlements that transformed their character but persisted, maintaining cultural continuities even as urban centres in the Indus mainstream declined.

Material culture and subsistence practices changed gradually, not catastrophically. Archaeobotanical records show transitions from wheat-barley agriculture to millet cultivation, a drought-tolerant crop. This shift emerged from centuries of interaction between climate, innovation, and cultural adaptation.

Farmers experimented. Knowledge accumulated. Agricultural practice evolved gradually.

Maritime trade, documented through seals recovered in Mesopotamia, provided economic buffering. Coastal settlements engaged in trans-Arabian commerce, supplementing locally stressed agricultural production with imported staples. External trade offered stability unavailable to purely terrestrial societies.

Gradual Metamorphosis and not Complete Collapse

We are no longer looking for a smoking gun of massacring marauders or a single catastrophic year of calamities. We are looking at trends, probabilities, and the slow, grinding friction of environmental change.

Harappans were neither victims nor eco-villains. They were a resilient and adaptive society.

The advancement from 2018 to 2025 exemplifies how science functions through iterative refinement rather than prejudiced assumptions.

The Harappan transformation emerges as a sophisticated process: hydroclimatic stress delivered in distinct episodes created adaptive pressures that populations met through migration, agricultural innovation, trade intensification, and institutional transformation. Rivers ran dry, but people adapted systematically.

That adaptation, documented across multiple scientific disciplines and archaeological evidence, tells a story richer than simplistic narratives – one of human resilience confronting genuine environmental stress and transforming civilisation through patient, centuries-long adjustment.

The paleoclimate records, studied so meticulously and with increased refinement, closes a chapter in Indian historiography while opening a more nuanced understanding of how complex societies respond to environmental stress and successfully reorganise when facing persistent hydro-climatic challenges.

In an era of modern global climate anxiety, there is perhaps more than one lesson in the Harappan metamorphosis.

Paper Reference: Solanki, H., Jain, V., Thirumalai, K. et al. River drought forcing of the Harappan metamorphosis. Commun Earth Environ 6, 926 (2025). Download the paper here.