Heritage

The Making Of Jaipur: The City That Forgot It Was A Failure

Deepesh Gulgulia

Dec 07, 2025, 08:00 AM | Updated 04:21 PM IST

Two months ago, I attended a three-day workshop, and during a session on urban planning, someone from the audience asked a simple question.

"What about Jaipur sir, is it a good model for Indian cities?"

The speaker smiled and replied in one line.

"Jaipur is a failed model, it is not sustainable at all."

I come from western Rajasthan (Bikaner). I had always thought of Jaipur as a proud, orderly city with straight bazaars and pink facades. I knew the basic textbook line that it was built by Sawai Jai Singh, but that was it.

Hearing someone call Jaipur a failed model felt odd, almost disrespectful. I did not have all the facts to counter him that day, so I did the only thing I could. I went back and started reading Building Jaipur: The Making of an Indian City by Vibhuti Sachdev.

This essay is the result of that curiosity. It is not about what Jaipur faces today. It is simply the story of how the city was imagined, drawn and built from zero to full form.

From hill fort to valley floor

Before there was Jaipur, there was Amber.

Amber was a hill fort and town tucked inside the Aravalli hills. In the picture of Amber from the book, you can see how the palace and settlement cling to the slopes, with very little flat land to spare. For centuries, this worked. Armies were smaller, trade was slower, and security was more important than comfort.

By the late 17th and early 18th century, the situation had changed. Trade routes between Delhi, Agra and the ports of Gujarat were becoming busier. Caravans of cloth, opium, metals and gems moved through the region.

The Kachhwaha rulers of Amber, who had long been allies of the Mughal court, were rich in land and political prestige, but they did not have a modern trading city.

Sawai Jai Singh the Second, who came to the throne at the age of 11, was not a typical ruler. Paintings of him shows a compact, thoughtful figure in a simple white jama, more scholar than warrior. He was a general, but also an astronomer who read Arabic and Persian texts, who built observatories in several cities, and who was obsessed with numbers and geometry.

Living in Amber, he had a very practical problem. The population was growing. The narrow streets inside the hill township were crowded. The water in the tanks and step wells was limited. There was no easy space to spread out markets or invite wealthy merchants to set up proper houses and shops.

The court histories say bluntly that the old capital had become too cramped and unhealthy.

So Jai Singh began to look down from the fort towards the open valley.

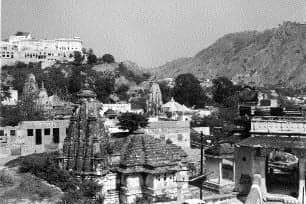

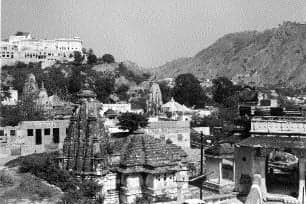

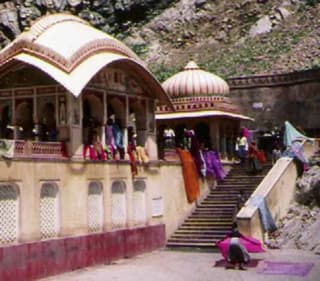

If you stand at Galta, the famous pilgrimage centre with the stone kunds, you can see what he saw. The colour photograph in the book, with women drying saris on the steps of the bathing tank, gives a sense of that landscape. Behind the temples, the hills fold gently and then drop into a broader plain.

This valley, between surrounding ridges, is where Jaipur would be born.

Choosing the site and the idea

Jai Singh did not simply walk out, pick a random flat ground and start building. He had two things in his mind at the same time.

One was political. He wanted a new capital that would announce the power of his house at a moment when Mughal authority was weakening. He wanted a city that could stand alongside the great capitals of the time.

The second was intellectual. He had grown up steeped in the old Sanskrit treatises on architecture and planning that are grouped under the term vastu vidya. These texts do not give ready-made blueprints, but they offer powerful concepts. They talk about how to divide space using mandalas, how to position temples and palaces, how to read the directions and the movement of the sun, and how to place different communities within a town.

Jai Singh found in his own court a man who could convert this theory into an actual plan. Vidyadhar Bhattacharya, an auditor from Bengal, was also a trained vastu scholar. The king and the architect formed an unusual partnership.

One brought political ambition and mathematical curiosity. The other brought textual knowledge and practical building experience.

Together, they began to walk and measure the valley below Amber.

The valley was not empty. There were streams that carried seasonal water. There were fields and small shrines. There was the sacred centre of Galta with its water tanks. The surrounding hills framed the space and also provided natural protection.

What Jai Singh and Vidyadhar needed was a way to inscribe an ideal diagram on this not-so-ideal land.

The invisible drawing on the ground

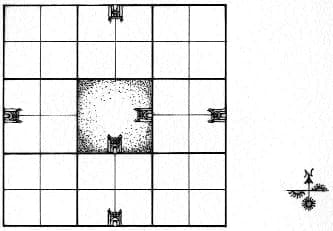

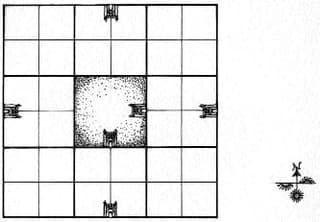

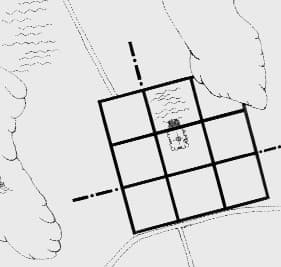

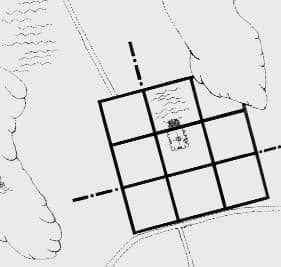

In the first chapter of the book, there is a simple but powerful diagram of a paradigm city. A square is divided into a grid. The centre is marked as the most sacred point. The palace, temples and bazaar streets are positioned according to rules that link each direction to specific deities and types of activity.

This is the mental toolkit that Jai Singh and Vidyadhar were using.

According to the vastu texts, a city should be aligned with the cardinal directions. At the same time, the square can be seen as a cosmic diagram, with each side, corner and central point associated with different gods and cosmic forces.

The most important part of this system for Jaipur was the grid of sixteen or sixty-four or even more squares, which could be simplified into a basic pattern of nine major blocks.

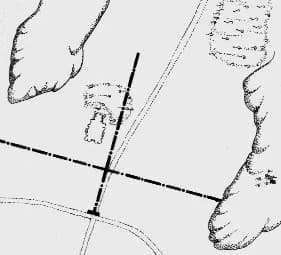

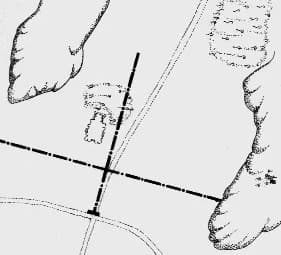

The book reproduces three small drawings on one page that perfectly show how Jai Singh's city was translated from idea to ground. In the first picture, you simply see the hills and two strong lines crossing each other. One line runs roughly east to west. The other runs from the hills down towards the plain.

In the second picture, the lines are multiplied. You see parallel strokes, which will become streets, laid out between the hills and the river. The valley is now imagined as a set of long strips, running in one direction, that follow the natural slope.

In the third picture, a square appears, rotated slightly with respect to the page. It sits snugly within the hills. Inside this square you see the grid of smaller rectangles, and in the centre a thicker cluster that will become the palace complex.

These images are like the storyboard of a film. First, there is only landscape. Then there are imaginary lines. Then there is a complete city.

The tilt and the nine squares

If you look at modern satellite images, you will notice that Jaipur's main bazaar does not run exactly east-west. It is tilted. Earlier writers guessed that the angle was around fifteen degrees. Later work suggested that it is closer to thirteen and a quarter degrees.

This tilt was not an accident. The king and his architect wanted to respect both the flow of the valley and the position of important shrines. The main east-west bazaar was drawn in such a way that it connected the chosen gate on the eastern side of the wall to the gate on the western side, while also aligning with sacred points in the landscape.

In simple terms, they rotated their square slightly so that it sat comfortably in the bowl of hills.

Within that square, they drew a grid that gave them nine large blocks. These nine sectors were symbolic as well as practical. In some traditions, they are linked to the nine forms of the earth or the nine treasures of the god Kubera. In Jaipur, one of the nine was distorted by the presence of the hills, so it effectively lies outside the perfect square.

Yet as a concept, the nine-part mandala remained.

From this diagram came the practical structure that every Jaipur visitor knows. There are three main streets running from east to west. They are intersected by three main streets running from north to south. At their crossings are large squares or chaupars, which once held water tanks and fountains.

Walls, gates and the royal spine

Once the square and the grid were fixed, the next task was to frame them. A city in that time was not complete without a wall. The wall of Jaipur is still one of its most striking physical features.

In the photograph of the city wall and its tiny market in front, you see a long rhythm of blind arches topped with obstacles, with a single arched opening that acts as a gate.

The wall served three purposes at once. It was defensive. It marked the boundary of royal authority. And it created a clear visual line that separated the ordered interior from the open countryside.

Seven main gates pierced this wall. Suraj Pol, on the east, looked towards the rising sun. Chand Pol on the west looked towards the setting moon. Ajmeri Gate and Sanganeri Gate opened towards the trading routes in those directions. Other gates connected to the hill roads and the pilgrimage routes.

Each gate had its own small temple and image on the outside or inside, so even while entering the city, people passed under the protection of a deity.

The most important street ran between Suraj Pol and Chand Pol. This became the king's ceremonial axis. On festival days, elephants, palanquins, royal guards and musicians moved along this route. On ordinary days, grain traders, cloth merchants and jewellers opened their shops along the same line.

The life of the city was strung on this spine.

From this main bazaar, side streets branched out towards the north and south. From every side street, smaller lanes penetrated deep into the residential quarters. If you stand on the roof of the Hawa Mahal, the view down the long bazaar that stretches away in a straight line, with the hills faint in the distance, gives a perfect sense of the clarity of this plan.

Filling the grid with people and work

A diagram of nine equal squares looks abstract. The real challenge is deciding who lives where, who sells what, and how the city breathes every day.

Here again, Jai Singh and Vidyadhar drew upon both texts and common sense. The vastu treatises talk about placing different castes and occupations in particular sectors of the mandala, according to the deity associated with that direction. At the same time, no ruler could ignore the practical need for convenience and security.

The result in Jaipur was a planned but flexible social geography.

Brahmins had their quarters in certain northern wards. Merchants occupied the central stretches along the bazaars. Artisans and craftspeople had specific blocks. There were areas dominated by metal workers, by potters, by cloth dyers and printers, by oil pressers.

The city became a living catalogue of skills.

The court histories mention that Jai Singh invited wealthy Jain and Vaishya traders from other towns and offered them land and tax concessions if they settled in the new capital. He also built havelis for the chiefs of his state in different parts of the city and then recovered the cost through a fixed share of their income.

This meant that each quarter had a powerful resident who cared about the state of the streets, the drains and the local markets. It also ensured that the aristocracy stayed close to the palace rather than building their own rival centres elsewhere.

The front of a Jaipur haveli, illustrated in the book, shows how these houses were integrated into the urban fabric. The ground floor has arched openings for shops, whose shutters would be pulled up each morning. The upper floors have projecting balconies with carved brackets and delicate stone screens.

A uniform cornice line runs along the whole street, so that even privately owned buildings contribute to a collective façade.

Water at the heart of the city

No city in semi-arid Rajasthan can be planned without thinking carefully about water.

The valley chosen for Jaipur already had a sacred water centre at Galta. The photograph of the bathing tank with temple pavilions and colourful cloths drying on the parapets captures how closely everyday life was tied to that source.

Jai Singh complemented this existing system with new structures inside the city.

At the two central squares of the grid, Badi Chaupar and Choti Chaupar, there were large rectangular tanks. Each had steps on all sides and fountains in the middle. These tanks were linked by underground channels to dams and reservoirs outside the wall. Rainwater from the surrounding hills and from the city's surfaces was guided into these storage points.

The city also had dozens of wells and step wells distributed across different wards. Together, they formed a network that acted as both a water supply and a social infrastructure. Women met while drawing water. Children played on the steps. Travellers rested in the shade.

The sound of water falling in the centre of the Chaupar, combined with the smell of flowers and incense from nearby temples and shops, formed the sensory backdrop of Jaipur's daily life.

It is important to see that water was not an afterthought. In the conceptual diagrams of the city, the squares and streets are not empty. They are imagined together with tanks, wells and gardens.

Jaipur's planners were working with a complete package that combined geometry, hydrology and social life.

The palace and the cosmic centre

In the mandala of a city, the most powerful point is the central space, the brahmasthan. For a great king, this point is the natural place for either the main temple, the palace or a combination of both.

In Jaipur, the City Palace and the temple of Govind Devji together occupy this sacred centre.

If you enter the palace complex from the side of the old city, you pass through gateways and courtyards that follow another, smaller set of mandalas. The image of the Ganesh Pol in the book gives a sense of this. It is not only a gate but an entire elevation composed as a symmetrical façade with arches, galleries and painted panels, crowned by domed kiosks.

Inside, the courtyards grow more refined and intimate as you move closer to the royal apartments.

The plan of a palace described in the old texts involves a series of concentric courts. The outer ones are for administration, storage and stables. The inner ones are for rituals and for the private life of the king and queens.

In one of the diagrams reproduced in the book, these courts are drawn as nested squares, each proportionally related to the one inside it. Jai Singh's palace at Jaipur follows the spirit of this system even if not every dimension matches the ideal.

Attached to the palace complex is the temple of Govind Dev. The image of Shri Govind with Radha, richly decorated, underlines how central this deity was to Jai Singh's religious and political programme.

Bringing the idol from Vrindavan to Jaipur and housing it close to the palace turned the city itself into a kind of expanded temple mandala, with the god at its heart and the bazaars and homes as the body of a sacred landscape.

Just outside the palace, Jai Singh built the Jantar Mantar, his famous observatory. The massive stone instruments here were not just scientific tools. They were also architectural statements about a ruler who could measure the heavens.

When you place the view across the city from Galta next to the photographs of the observatory, you get a strong sense that this was a city whose very plan grew out of the king's obsession with the sky and with order.

A new type of Indian capital

By the time the main streets were laid, the walls completed, the palace partly built, and the first havelis allotted, Jaipur was ready to function.

Caravans began to arrive. Merchants opened shops on the bazaars. Artisans set up their workshops in the assigned quarters. Pilgrims came to see the new temple of Govind Dev. Farmers from surrounding villages brought their grain and milk and ghee.

The thakurs of the state came to live in the grand houses that had been built for them. The king could now ride out from his palace, pass under painted gateways, through straight streets lined with colonnades, and look upon the physical proof of his ambition.

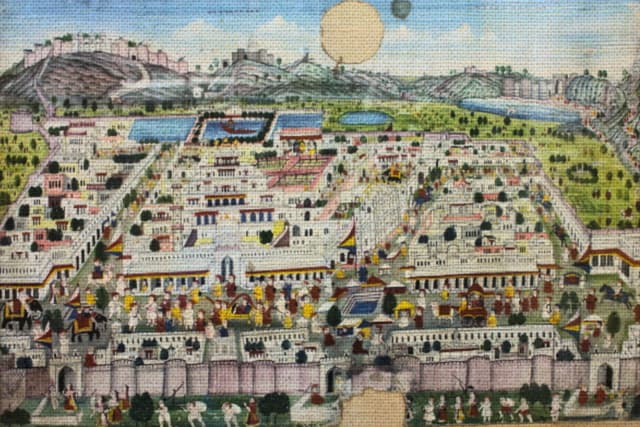

The grid of streets is clear. The palace complex is bright at the centre. Small pictorial motifs of elephants, camels and carts populate the margins.

It looks like a cosmic diagram that has come alive.

For its time, Jaipur was something new in India. It was neither a purely sacred town built around a single great temple, nor a fort city that grew organically over time. It was a planned commercial capital that combined Rajput royal culture and an older vastu imagination into one project.

Returning to that casual remark

When I think back to that workshop, to the speaker who dismissed the Jaipur model as a failure, I now hear the sentence differently. If someone looks only at the current unplanned growth outside the old walls, they may feel the city has failed. That is a different conversation.

If we look only at how the city was conceived and built in the early eighteenth century, Jaipur is not a failed model. It is a rare example of a king and an architect patiently translating a dense body of theory and a complex landscape into an actual living city.

The straight bazaars that so many of us have walked through are not just lucky accidents. They are the visible traces of an invisible diagram drawn long ago in the minds of Jai Singh and Vidyadhar, picked out with survey ropes on the dust of a valley floor, and then raised in brick, lime and stone.

That, in itself, is a story worth telling.

Deepesh Gulgulia is a Law student. He tweets at x.com/@deepeshgulgulia.