Ideas

Forget Macaulay's Minute. Have You Heard Of The 'Madras System' That Shaped British Schooling?

Aravindan Neelakandan

Nov 27, 2025, 01:44 PM | Updated 02:09 PM IST

For nearly two centuries, the historiography of India has been held captive by a narrative of benevolent modernisation. This colonial intervention, epitomised by Thomas Babington Macaulay's 1835 Minute on Education, claims to have shattered the stagnation of a superstitious, backward civilisation and ushered in an age of rational progress under British tutelage.

But what if the story we have been told is not just incomplete, but deliberately inverted?

The Irony Britain Does Not Want You to Know

Here is a remarkable historical irony that shatters the colonial narrative: while Britain was destroying India's indigenous education system, it was simultaneously importing Indian pedagogical methods to educate its own poor.

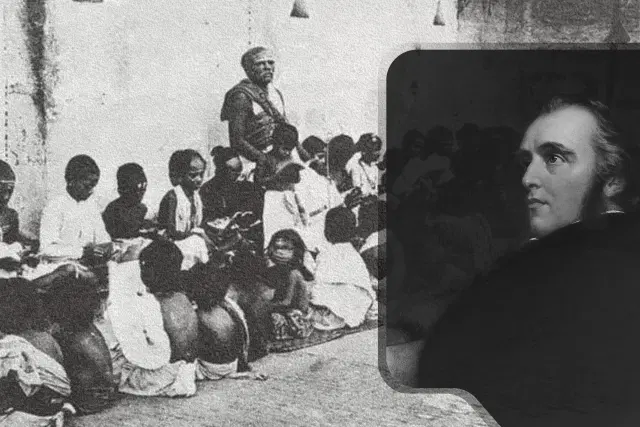

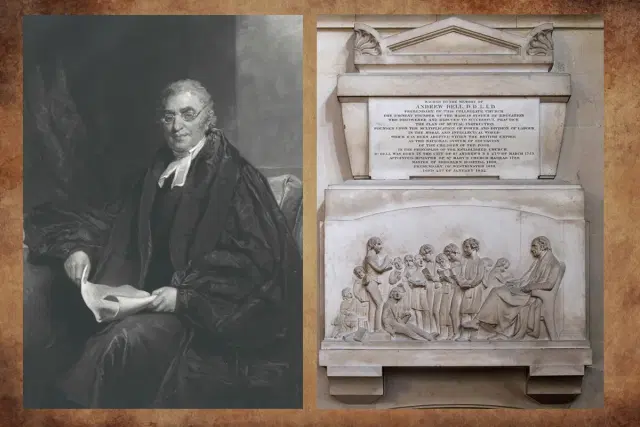

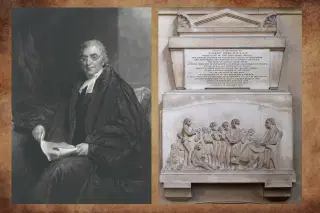

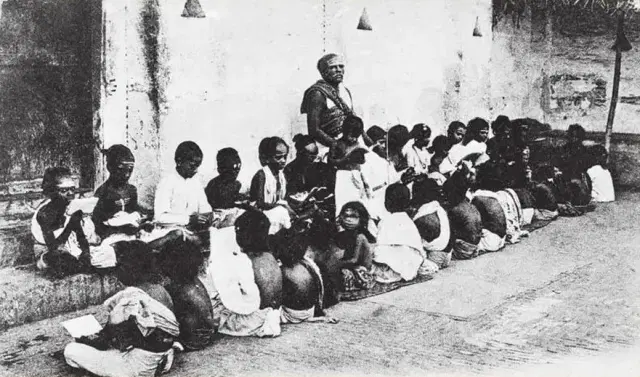

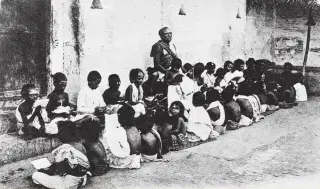

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, British educators Andrew Bell and Joseph Lancaster, inspired by village schools in South India where older students taught younger ones under the teacher's supervision, pioneered the monitorial system, initially called the 'Madras System', to address the lack of affordable mass education in England.

Bell developed the Madras System after observing Indian practices, which became foundational for British mass education. This system enabled a single teacher to oversee hundreds of pupils efficiently by employing peer teaching, a model based on Indian village schools, which democratised learning and greatly expanded literacy in Britain at minimal cost.

England publicly, albeit indirectly, acknowledged its 'debt to Indian pedagogics' through memorialising Bell's contribution in Westminster Abbey, recognising that this model had become the basis for educating the English poor.

Meanwhile, in India itself, the vibrant, decentralised system was actively starved, rendering late nineteenth century India far more illiterate. The Indian education system was essentialised by the absence of scientific knowledge and not its locally funded, decentralised features.

This stunning contradiction reveals the true nature of what came to be known as the Macaulay System of Education.

More Than Education: A Civilisational Psyop

The Macaulay System of Education (MSE) was far more than just a new pedagogical infrastructure. It functioned as a systemic proto psyop but on a civilisational scale. A mechanism of epistemological apartheid meticulously engineered to erase indigenous knowledge, institutionalise civilisational hierarchy, and create a permanent class of elite and powerful cognitive intermediaries whose cultural loyalties were redirected from their own milieu to the imperatives of the coloniser.

The MSE did not merely educate; it engineered a split personality within the Indian psyche, and in the long run, it continues to create in academia, media and polity a United Front of forces hostile to Indian civilisation that continues to hold indigenous society under siege.

The Fabricated Darkness Before British Light

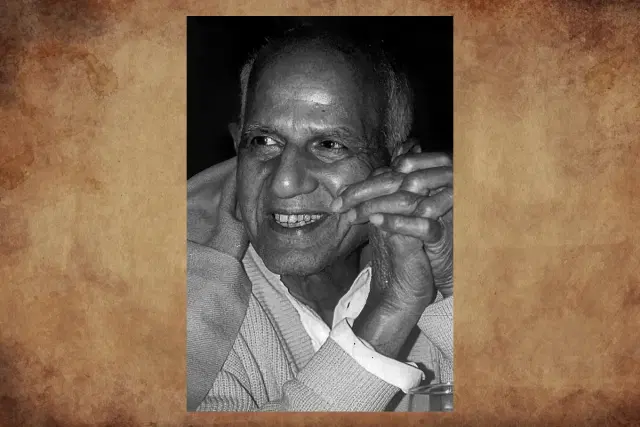

A central pillar of the colonial justification for the MSE was the fabrication that pre British India was a land of darkness, a British equivalent of jahiliya of Islamist theology, illiteracy, and Brahminical exclusivity. For the new system to be accepted as a saviour, the old system had to be demonised. However, colonial archival records, meticulously reconstructed by the Gandhian historian Dharampal (1922 to 2006), have falsified this narrative.

Data from the Madras Presidency (c. 1822 to 1825) shatters the assumption that education was the sole preserve of the twice-born. The archives indicate a vibrant, inclusive educational landscape.

Furthermore, the indigenous curriculum was not merely religious but deeply practical, teaching reading, writing, arithmetic, accounting, and trade mathematics alongside ethics. It was a system designed to support a complex agrarian and artisanal economy.

The students were not merely learning scripture; they were learning the skills necessary to participate in the economic life of their communities. This challenges the caricature of Indian education as purely metaphysical and detached from reality.

The collapse of this 'Beautiful Tree' was not due to its inherent obsolescence but was an engineered economic outcome of British revenue policies. The indigenous system relied on revenue assignments, shares of the village harvest or land grants traditionally set aside for the teacher. This was a system of direct community funding that ensured the teacher was accountable to the village, not a distant state bureaucracy.

The British revenue settlements (Ryotwari and Zamindari) centralised revenue collection, extracting the surplus that previously circulated within the village economy. By refusing to recognise these traditional grants as legitimate, and by redirecting state funding exclusively to the new English medium institutions, the colonial state starved the indigenous system, instead of allowing its own upgradation and modernisation.

Mahatma Gandhi, speaking at Chatham House in 1931, famously articulated this destruction:

The British administrators, when they came to India, instead of taking hold of things as they were, began to root them out. They scratched the soil and began to look at the root, and left the root like that, and the beautiful tree perished.

This was not passive neglect; it was active resource deprivation. The widespread illiteracy that characterised late nineteenth century India was, therefore, a result of British rule, not the condition it inherited. The MSE did not fill a vacuum; it created one by destroying a thriving ecosystem and then offering a meagre, elitist substitute.

Macaulay's Operational Order for Civilisational Lobotomy

Thomas Babington Macaulay's 1835 Minute, therefore, functioned as the operational order for a civilisational lobotomy. Its explicit goal was to create a class of intermediaries: Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals and in intellect. This was the Filtration Theory, which posited that Western knowledge would filter down from this anglicised elite to the masses. In reality, it created a hermetically sealed cognitive elite, severed from the indigenous population.

Did Macaulay Really Bring Science?

One of the most insidious myths of the MSE is that it introduced science to a superstitious land. In reality, the colonial state actively suppressed indigenous scientific inquiry. The British viewed India merely as a source of raw data, botanical specimens, geological surveys, and census figures, to be synthesised by theorists in London. The native was deemed capable of observation but incapable of higher order reasoning.

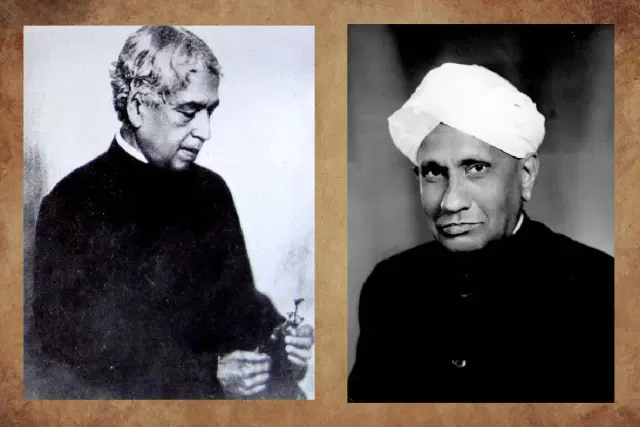

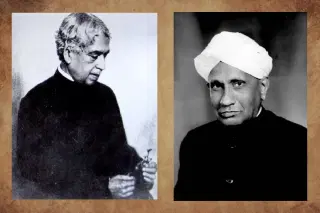

The Royal Society and its Indian Advisory Committee explicitly stated that Indian students should act as consumers of science, not producers. This policy is best exemplified by the treatment of Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose.

Despite his genius, Bose was denied access to laboratories reserved for Europeans and was forced to conduct groundbreaking research on electromagnetic waves in a dilapidated abandoned room. Crucially, he built his equipment with the help of local tinsmiths, a reliance on indigenous craftsmanship inherited from his father Bhagwan Chandra Bose, who had famously bankrupted himself supporting the nascent Swadeshi industry.

Thus, Bose's success was not a product of colonial tutelage, but a defiant reclamation of the very native capability the MSE sought to erase.

Another instance is the research work of Chandrasekara Venkata Raman. He became Asia's first Nobel Laureate in physics for his discovery of the Raman Effect. He did this work not in any colonial laboratory but in the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (IACS).

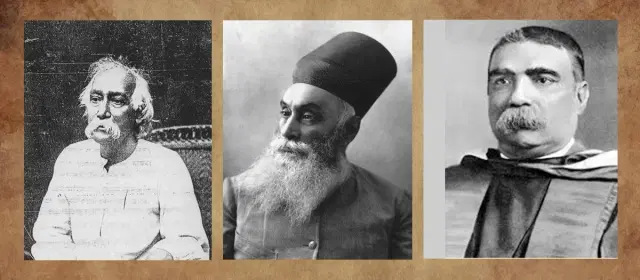

IACS was established in 1876 by Dr Mahendra Lal Sircar in Calcutta as an indigenous national body, autonomous from British government influence and discrimination, to foster an independent Indian scientific community and dispel the myth that Indians were incapable of original scientific research.

Thus, when supporters of the MSE show J C Bose, C V Raman, or S N Bose as proof of the MSE's success, they overlook the reality: these men succeeded despite the system. Their achievements were acts of indigenous agency, a manifestation of the Swadeshi spirit, often conducted in institutions founded by Indians to bypass colonial inertia.

Many pioneers of Indian science, including Jamsetji Tata and Asuthosh Mukherjee, accepted modernity, but they were categorical in their rejection of the core axiom of the MSE, the supremacist civilisational hierarchy, even when framed in benign terms.

The Myth of Macaulay as Social Justice Saviour

A pervasive defence of the MSE is that it brought social justice and equality to a caste ridden society. It is argued that without the MSE, India would have remained mired in medieval hierarchy. However, a deep analysis of successful social emancipation movements reveals that the single common denominator was often a non MSE value system.

Perhaps the single most incisive argument against the notion that the MSE resulted in social emancipation was put forth by Rao Bahadur M C Rajah (1883 to 1943), a contemporary of Dr Ambedkar and a formidable Hindu leader of the oppressed in Madras. His surgical critique of the educational system introduced by the British challenges the simplistic notion that the imposed colonial education system was an unmitigated blessing for the downtrodden.

In his landmark book, The Oppressed Hindus (1925), Rajah argued that the British education system, modelled on the University of London, was a soulless machine. He wrote:

The products of that system were types that had cut themselves adrift from all their old moorings of 'Dharma and Ahimsa' and had not assimilated the British ideals of Justice and Fairplay. They were with a few honourable exceptions, merely free lances abroad armed with a smattering of Western knowledge in a vast population of varying degrees of culture from the fifth century to the fifteenth and mostly took to the predatory professions and fished in troubled waters of their own creation.

Rajah observed that because the colonial bureaucracy was staffed largely by upper castes, the new education simply armed traditional elites with new weapons, the courts, the police, and revenue administration, to exploit the uneducated masses more efficiently. In his view, the MSE modernised oppression rather than ending it.

Furthermore, Rajah critiqued the British legal system for giving legal recognition to certain social customs and usages which enlightened public opinion regards as unjust, anti social and irreligious. He realised that the British policy of non interference was effectively a strategy to preserve the status quo of oppression to maintain imperial stability.

While praising individual British parliamentarians for their commitment to the uplift of the downtrodden, Rajah launched a precise attack on the systemic tools used to block indigenous pathways to emancipation; at the core of this institutional mechanism was the MSE.

Bodhisattva Ambedkar: Churning the Smritis and Dharma Shastras

To portray Dr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar merely as a secular rationalist who repudiated Indian tradition is to embrace a reductionist fallacy. In truth, Ambedkar regarded religion as a profound inner force, far more critical to the formation of human character than formal education alone. Addressing the Railway Workers' Conference in 1938, he articulated this conviction:

Character is more important than education. It pains me to see youths growing indifferent to religion. Religion is not opium as is held by some. What good things I have in me or whatever benefits of my education to the society, I owe them to the religious feelings in me.

Dr Ambedkar's relentless battle against injustice and his quest for social emancipation bore the distinct imprint of his patron, Sayajirao Gaekwad of Baroda. The Maharaja, a visionary ruler, had earlier employed and been profoundly influenced by Sri Aurobindo.

In his writings, Sri Aurobindo consistently championed the triune ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity, yet he sought to excavate these values from within India's own indigenous heritage rather than importing them as foreign constructs.

This subtle but deep intellectual current is evident in Dr Ambedkar's philosophy, who similarly posited these qualities as the spiritual foundation of Indian nationhood, insisting they be derived not from Western political thought, but from the timeless wisdom of the Upanishads.

Did Dr Ambedkar see colonial institutions, of which the MSE was a cognitive pillar, as actively fostering social stagnation? Such a revelation comes out clearly in his debates on the Hindu Code Bill.

When conservative critics argued that granting property rights to daughters was antithetical to Hindu tradition, Ambedkar executed a profound intellectual manoeuvre. The very man who had symbolically burned the Manusmriti in his youth now invoked the authority of the Smritis of Manu and Yajnavalkya to assert women's rights.

In doing so, he launched a scathing critique of the British Privy Council, exposing how its rigid legal interpretations had selectively fossilised regressive customs while suppressing the progressive elasticity inherent in the ancient texts. He remarked:

I am very sorry for the ruling which the Privy Council gave. It blocked the way for the improvement of our law. The Privy Council in an earlier case said that custom will override law, with the result that it became quite impossible to our Judiciary to examine our ancient codes and to find out what laws were laid down by our Rishis and by our Smritikars.... so far as the daughter's share is concerned, the only innovation that we are making is that her share is increased and that we bring her in the line with the son or the widow. That also, as I say, would not be an innovation if you accept my view that in doing this we are merely going back to the text of the Smritis which you all respect.

This assertion carries profound implications that extend far beyond legal technicalities. Bodhisattva Ambedkar implicitly posits that without the calcifying intervention of colonial rule, Indian civilisation possessed the innate vitality to churn out progressive, egalitarian, and pro women jurisprudence from within its own value systems.

This critique of the Privy Council cuts to the heart of the Macaulay System of Education as well. Both institutions operated on the premise that indigenous tradition was static and regressive, requiring external correction. In reality, by freezing fluid customs into rigid laws and displacing native wisdom with alien dogmas, these colonial interventions manufactured the very social stagnation they claimed to cure, arresting the natural, reformist evolution of the society.

Breaking Free of the Longest Psyop in History: Macaulayism

The Macaulay System of Education was not a benevolent gift of modernisation; it was an instrument of civilisational subordination which served the colonial interests and continues today as a tool in the larger civilisational war.

The deepest level of colonisation was not merely the extraction of wealth or the destruction of indigenous schools; it was the implantation of the belief that Indian civilisation is inherently anti science, anti reform, anti egalitarian, and anti humanistic.

Crucially, the necessity of dismantling this system is not an argument against the English language itself, but against the colonial consciousness it often carries. As the historian Sitaram Goel, incisive critic of Macaulayism, has forcefully pointed out, the battle is epistemological, not linguistic.

Thus, the English of Swami Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo was Dharmic, decolonising, and liberating, a resounding trumpet of India's spiritual sovereignty. In stark contrast, even the Sanskritised, pure Hindi of a figure like Rahul Sankrityayan functioned as a tool of colonisation, smuggling in the anti democratic and rigid categories of Marxism.

The MSE is defined not by the language it speaks, but by the worldview it imposes.

The MSE trained Indians to view their own heritage as a site of oppression, obscuring the reality that the Indian reform movement is the single largest sustained socio spiritual reform movement anchored in the tradition of an ancient civilisation in the entire history of humanity.

True and deep decolonisation, therefore, is not about accepting social stagnation as tradition, which is precisely what the rigid colonial frameworks wanted Indians to believe. Rather, it requires breaking the hypnotism imposed by the Macaulay System of Education.

We must reclaim the indigenous capacity for self correction and press ahead for bold reform movements, rooted not in colonial imitation, but in the dynamic, churning spirit of Indian civilisation itself which is Sanatana Dharma.