Ground Reports

Why NEET-PG Cut-Offs Hit Zero - and What It Reveals About India's Medical Education System

Ankit Saxena

Jan 27, 2026, 11:20 AM | Updated 03:15 PM IST

Zero percentile.

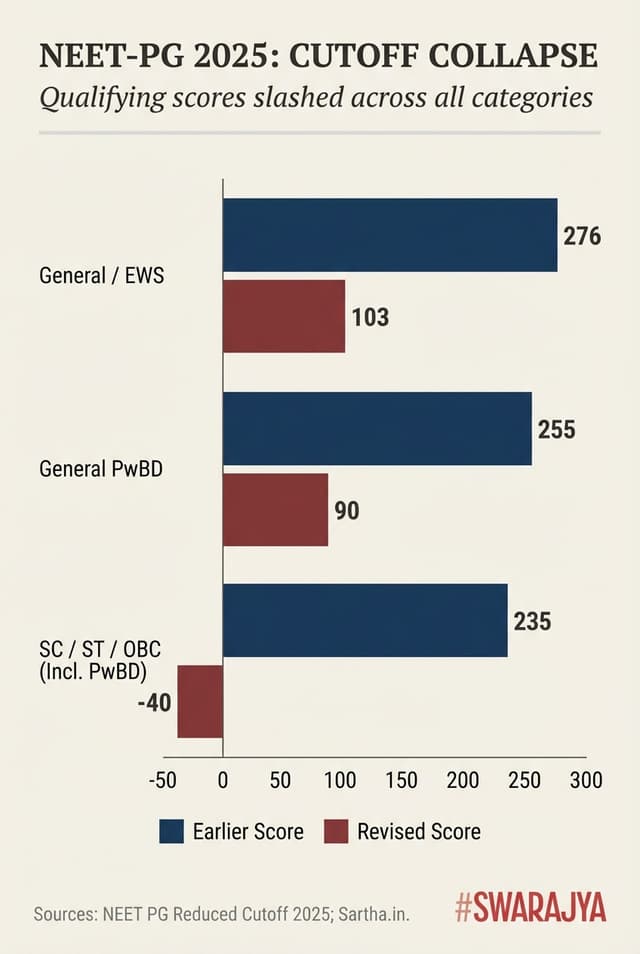

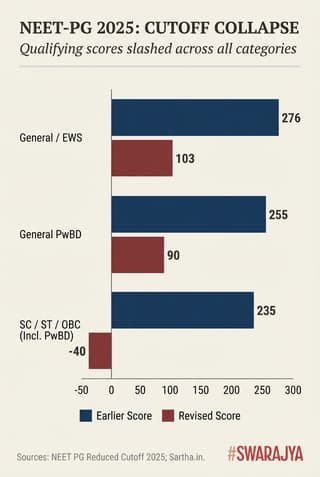

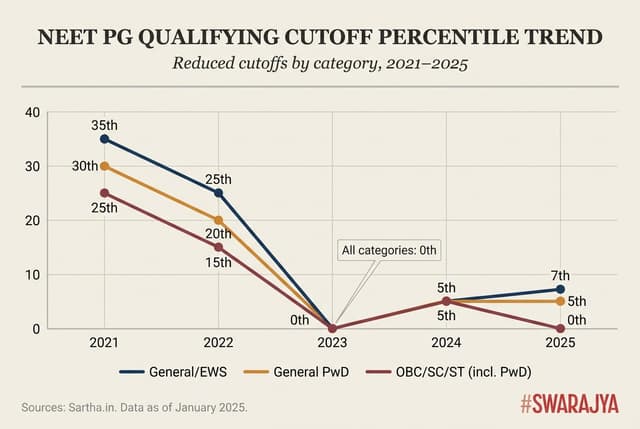

That's the new qualifying threshold for NEET-PG 2025 for SC, ST, and OBC candidates in the third round of counselling. For the general category, the National Board of Examinations in Medical Sciences (NBEMS) reduced the qualifying percentile from 50 to 7.

This reduction means that candidates with zero or even negative marks can now apply for some postgraduate medical seats. The announcement triggered widespread disbelief. How could an entrance examination for specialist medical training set the bar at, effectively, nothing?

The timing adds to the dissonance. In 2024, NEET was under scrutiny for the opposite problem: the undergraduate examination saw suspiciously high cut-off scores, including multiple candidates achieving perfect 720 out of 720, alongside allegations of paper leaks.

That controversy centred on inflated performance. This year's concerns the postgraduate examination, and the issue has inverted: not excessively high cut-offs but their dramatic reduction to fill vacant seats.

NEET-PG is India's mandatory, single-window entrance examination for admission to postgraduate medical programmes (MD, MS, and PG Diploma courses, as well as DNB and NBEMS Diploma) across both government and private institutions. DNB, or Diplomate of National Board, is a postgraduate medical qualification awarded by NBEMS, considered equivalent to MD/MS degrees for most purposes.

The most recent examination was conducted on 3 August 2025. For the 2025-26 academic year, India offered more than 70,000 postgraduate medical seats.

The zero-percentile threshold exists because, after two rounds of counselling, more than 18,000 of those seats remained unfilled, including 9,000 under the All India Quota. To fill these vacancies in the third round, authorities relaxed eligibility rules.

However, the question is why so many seats went unfilled in the first place.

The Vacancy Puzzle: Why Seats Remain Unfilled Despite High Demand

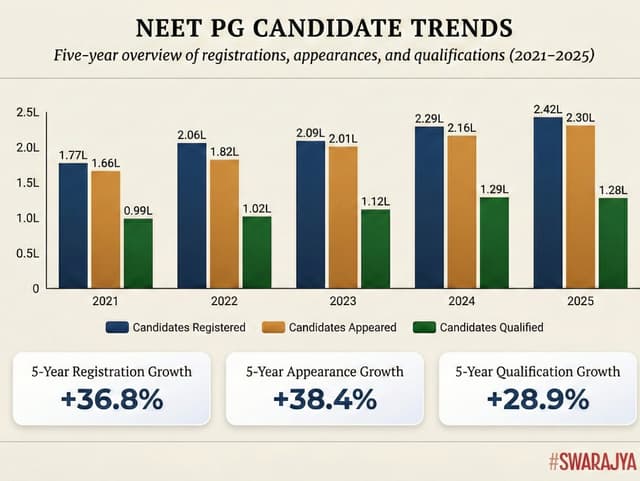

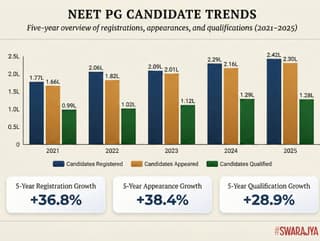

At a time when many countries that students once preferred for medical education are facing instability, India continues to see vacant postgraduate seats. The vacancy problem is not about the number of candidates appearing. Each year, 1.5 to 2.3 lakh candidates appear for NEET-PG.

On paper, supply and demand align. But the problem has shifted from the number of seats available to the quality and practicality of those seats: a mismatch of composition rather than quantity.

These 18,000 seats are not randomly distributed. They cluster in predictable places, and understanding where they are explains why filling them has proven difficult, and why lowering cut-offs may not solve the problem.

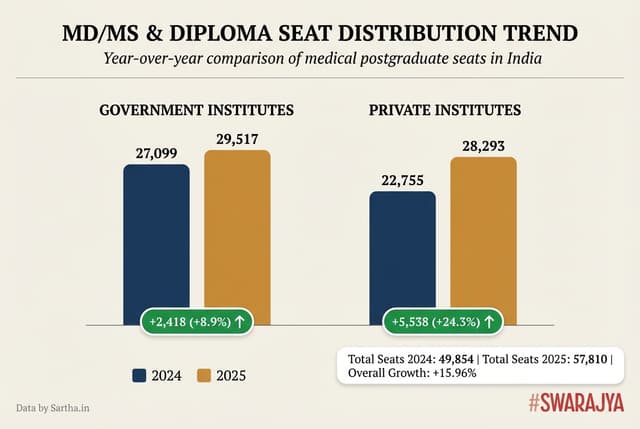

India's expansion of postgraduate seats, with government plans to add 75,000 more for both UG and PG, has occurred predominantly through private institutions. The number of PG candidates and medical seats has steadily increased in recent years, which is generally a positive development.

However, this growth has brought challenges. Most newly added seats are in private colleges, which charge fees that can run twenty times higher than government institutions. A seat costing Rs 50,000 annually at a government college might cost Rs 10-40 lakh, or even higher at a private one.

The Real Barriers: Cost, Quality, and Career Prospects

Understanding this from the candidates and medical counsellors, they state, "Most vacant seats are in private colleges, and to fill them, the authorities keep lowering the cut-offs."

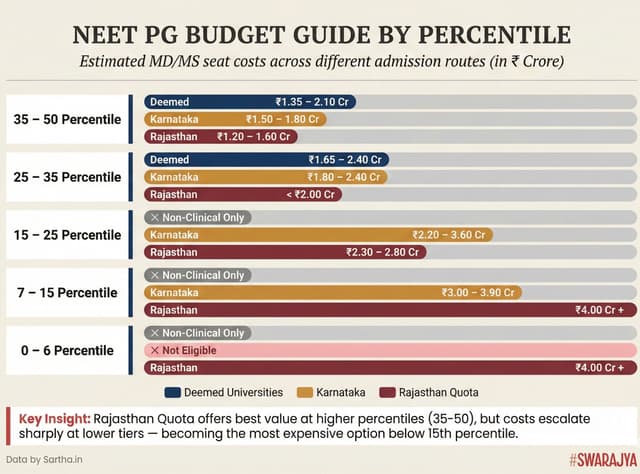

According to Sartha, a college guidance and counselling platform, an analysis of available data shows that lower cut-offs correlate with higher seat costs in private colleges.

"High fees remove merit from the equation because not everyone can afford them. Reducing cut-offs then opens up seats for those with affordability rather than merit," Akash Satyam from Sartha told Swarajya.

"This is one of the main reasons seats continue to remain vacant. Every time the cut-off is reduced, the cost of the seat goes up."

The second cluster of vacancies falls in non-clinical disciplines.

Clinical branches (Medicine, Surgery, Paediatrics, Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Dermatology, Radiology, Psychiatry) involve direct patient care. Non-clinical branches (Anatomy, Physiology, Biochemistry, Pharmacology, Microbiology, Pathology, Community Medicine) focus on research, academia, administration, and laboratory-based work.

While 70-80 per cent of PG seats are in clinical branches, many vacant seats are in non-clinical subjects, according to Dr Jayesh Ghanchi from Sartha.

"As qualified doctors, most candidates want to specialise in clinical fields," Dr Jayesh explained. "Non-clinical branches do not allow independent practice and are mostly limited to teaching or research roles. This means fewer opportunities and slower financial growth."

For doctors who have completed MBBS training, accepting a non-clinical seat can feel like foreclosing their options.

Third, some clinical seats also remain vacant, particularly in peripheral government hospitals and district hospitals. Candidates cite challenges including limited clinical exposure, low stipends, and weaker career prospects. "This is the standard situation across institutions in any discipline in India," candidates noted.

Many prefer to take a drop year, choose non-clinical seats temporarily, or continue preparing for the next attempt rather than accept these positions.

Administrative issues add another layer. During counselling, not all colleges and seats are approved by the Medical Counselling Committee (MCC) before the first round. Many seats are approved only by the second or third round, leaving candidates uncertain and waiting for better options.

"This leads to seat-blocking and the stuck payments of confirmation fees, which further complicates the process for students," Dr Jayesh added.

The Administrative Push to Fill Seats: A Quick Fix?

Officials defending the threshold reduction make a straightforward argument. All NEET-PG candidates are already MBBS graduates who have completed recognised medical degrees and compulsory internships. They are fully qualified medical practitioners eligible for postgraduate training.

The main purpose of NEET-PG and its counselling process, officials say, is to ensure available seats are fully utilised, more specialists are trained, and the shortage of medical professionals is addressed. Leaving a large number of seats vacant goes against this objective and wastes valuable educational resources.

The logic is simple: if qualified doctors exist and empty seats exist, the solution is to lower barriers until the two meet.

Candidates see it differently. "While cutoff reduction is to fill seats, this does not justify or validate the points the officials are making," one candidate told Swarajya.

"Even though we are qualified doctors, NEET-PG is the gateway to specialisation. The examination is necessary to assess merit and capability, and it also gives candidates a fair chance to secure their preferred colleges and courses."

"If that was the case, why do we even need to conduct the examination then?" the candidate added. "This approach increasingly makes it seem like seats are being allocated not on merit, but on the basis of how much a candidate can afford."

A Pattern, Not an Anomaly

This is not the first time cut-offs have been reduced to complete the admission process.

According to another candidate, cut-offs have been reduced in previous years as well, largely in proportion to the increasing number of seats added each year. However, what is being overlooked are the deeper issues that need to be addressed.

A similar approach was taken in 2023 to fill vacant seats. The pattern suggests a structural issue rather than an anomaly.

But is lowering cut-offs the only solution, especially when it shifts the focus from merit to simply filling seats?

"If these issues are not addressed properly, it will gradually reduce the quality of specialised doctors being trained. In the long run, this will affect the country's healthcare system," Dr Jayesh adds.

Addressing the root causes would require changes at multiple levels.

At the counselling level, the MCC should announce the full list of available seats at the start so candidates are not left waiting for later rounds. "This would help candidates plan better and improve the overall counselling process. The same issue exists at the UG level as well," healthcare experts said.

On private college seats, there is a need to review the expansion happening through private institutions to avoid these seats increasingly functioning as budget-based rather than merit-based.

"It is important to reserve at least 15-20 per cent under a government quota in private colleges," Akash said. "This would allow meritorious students to enter these colleges and make the system fairer."

At the same time, equal attention should be given to increasing the number of government college seats each year.

Non-clinical disciplines need reform to become more than a last resort. "With already MBBS-qualified candidates, non-clinical courses should continue to give some level of clinical exposure and continued involvement in healthcare work," Dr Jayesh suggested.

Another opportunity lies in developing hospital administration pathways that combine medical training with management skills, an area becoming increasingly important in India's expanding healthcare system. With such attention, it would be easier to make non-clinical seats more attractive and valuable.

Until these structural issues are addressed, the cycle of lowering thresholds to fill seats is likely to continue, raising uncomfortable questions about whether India's pathway to producing specialists is being shaped more by economics than by excellence.