Science

The State's Heretic: A Scientist Who Starved So The World Might Eat

Aravindan Neelakandan

Jan 26, 2026, 07:00 AM | Updated Jan 26, 2026, 12:29 AM IST

The Marginalian, formerly known as Brain Pickings, is an online portal for curated thought. Founded by Maria Popova, it is a digital haven where art, science, philosophy, history, and literature converge, offering readers a kaleidoscopic matrix of ideas and perspectives. Beyond being merely a portal, The Marginalian extends its reach through a newsletter, a conduit for deeper engagement with its rich content.

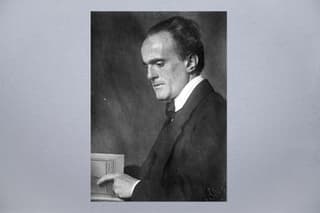

On 20 March 2025, the newsletter featured a poignant exploration of the life and work of Nikolai Vavilov, the visionary geneticist and plant breeder. Vavilov, a scientist of profound humanism, nurtured a dream of a world free from hunger, dedicating his expertise to collecting and preserving diverse seeds, particularly indigenous varieties. As the newsletter articulated:

There must be wild varieties of common agricultural plants with different genes that make them more resilient than their farmed cousins — genes that could be used to strengthen agricultural crops by breeding stronger species that would feed humanity even through droughts and freezes. He called them his miracle plants. It wasn’t just an idealist’s dream — he knew the science that would make it a reality, and he would devote his life to it.

The Marginalian's newsletter, in its exploration of Nikolai Vavilov's life, laid bare the stark contrast between his unwavering scientific dedication and the tragic reality of his demise under the Soviet regime. This systematic silencing, a chilling example of ideological suppression, extended beyond Vavilov, impacting countless others.

In a world governed by reason and empathy, his legacy would have been celebrated as a beacon of scientific integrity and planetary ecological humanism, a figure transcending the artificial barriers of ideology and profit-driven greed. Instead, he remains a shadow, a casualty not only of Marxist state censorship but also of a world that often ignores inconvenient truths that critique prevailing power structures.

His vision, a call for global collaboration driven by empathy and scientific advancement, remains profoundly relevant, a stark reminder of what humanity loses when it prioritises ideology and profit over truth.

The iron grip of Marxist ideology on Soviet science did not emerge suddenly and absolutely with the coming of the Bolshevik era. After 1917, as Lenin's party solidified its power, a tentative accord was struck between the state and its biologists. The latter, initially distrustful of Lenin's government, discovered they could navigate the new political landscape, capitalising on the regime's need for a 'scientific' veneer to secure and expand their research institutions.

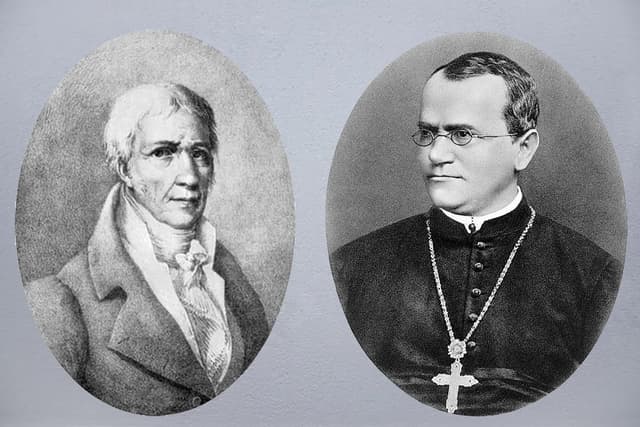

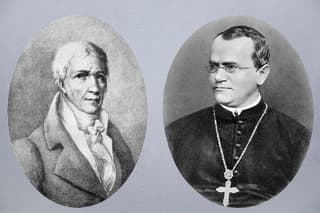

This delicate truce, however, unfolded against the backdrop of a profound scientific debate that captivated biologists worldwide: the clash between Mendel's principles of innate hereditary factors and Lamarck's proposition of transmissible acquired characteristics. As the fierce, early twentieth-century debate among biologists over the mechanism of evolution reached the USSR, the seeds of a future where political ideology would dictate scientific truth were already beginning to sprout.

Soviet geneticists, too, made impressive contributions to this international debate. In 1920, Vavilov wrote about what he called 'the law of homologous series in hereditary variation,' showing that plant evolution follows predictable patterns. This suggested, without stating it directly, that evolution might be guided in a specific direction.

In 1921, Filipchenko published an expanded version of his 1915 brochure on Variability and Evolution, which advocated a mutationist view of evolution combined with guided evolution (orthogenesis). Two years later, he produced a lengthy analysis of 'the evolutionary idea in biology,' again siding with orthogenesis and mutationism. In 1922, Koltsov published an article on the 'formation of new species and the number of chromosomes,' which also advanced a mutationist concept of species formation.

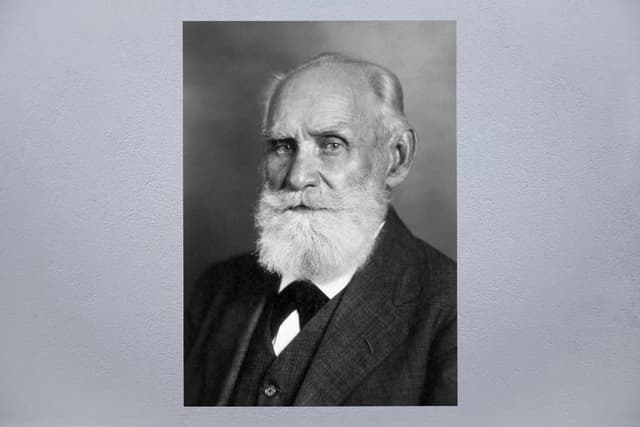

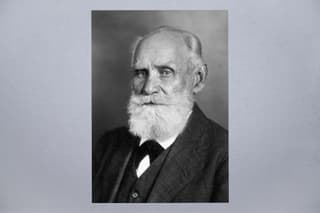

At the same time, Neo-Lamarckian Soviet biologists provided a strong scientific challenge to geneticists. One major convert to the Lamarckian concept of heredity was Ivan Pavlov, then the only Russian Nobel Laureate in science (physiology).

After studying the work of his assistant, Nikolai Studentsov, he became convinced that acquired Pavlovian conditioning could be transmitted across generations. The initial experiment proved difficult: establishing the conditioned reflex in the first mouse required 298 repetitions. However, its offspring, the first generation, learned the reflex in only 114 repetitions. The second generation required just 29, the third only 11, and the fourth a mere 6 repetitions. Studentsov concluded that the acquired reflex had become hereditary.

Pavlov announced these results on his international lecture tours, and in 1923 they were reported in the prestigious Science magazine. Later, however, Soviet geneticists showed Pavlov that it was not the mice that were learning faster, but Studentsov who was improving his skills at conditioning them. Thus, for a time, the debate remained healthy and rested on the scientific grounds of falsifiability and repeatability.

While this scientific debate unfolded, the Soviet Union undertook a campaign to inculcate its citizens with Marxist doctrines. Scientists were a special target group for being groomed in dialectical materialism as the only true philosophy of science. In 1924, the year Lenin died, the Timiriazev Biological Institute was renamed 'the Timiriazev Scientific Research Institute for the Study and Propaganda of the Scientific Foundations of Dialectical Materialism'.

By 1926, the ideological commissars of Marxism had decided that Mendelian genetics was flawed because it was reactionary, idealistic, and fatalistic, while the Lamarckian framework was in alignment with Marxism. That year, the USSR extended an invitation to the Austrian biologist Paul Kammerer, who had astonished the world by claiming he had conclusively proved the inheritance of acquired characters in his midwife toads.

Later examinations revealed that the toads were found to have been injected with India ink to create this effect, and Kammerer committed suicide. Though it was possible that Kammerer could have indeed discovered an epigenetic phenomenon, the problem was that there was definitely an injection of India ink, a fraudulent attempt to enact repeatability either by Kammerer or by one of his over-enthusiastic assistants. Author Arthur Koestler wrote a sympathetic account of the controversy claiming that Kammerer was innocent.

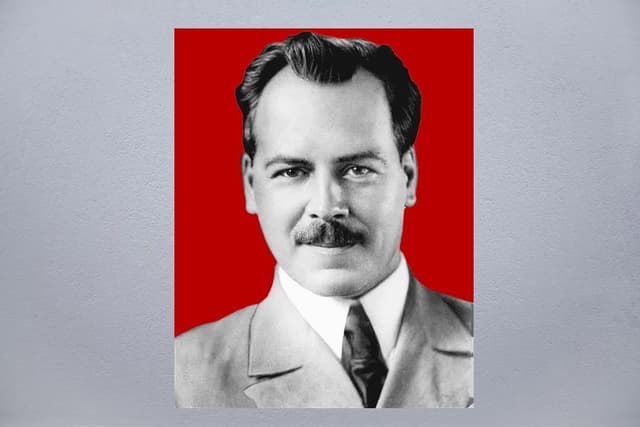

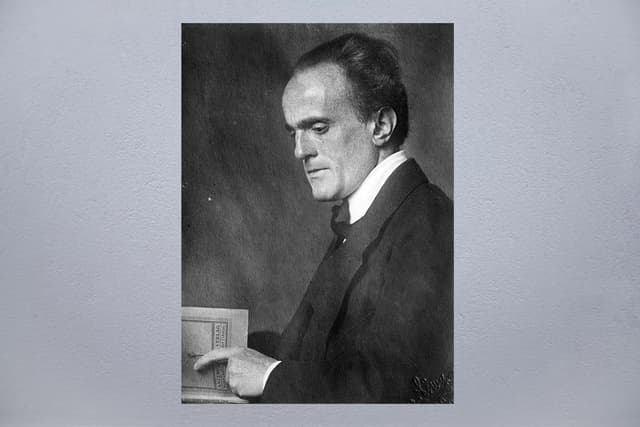

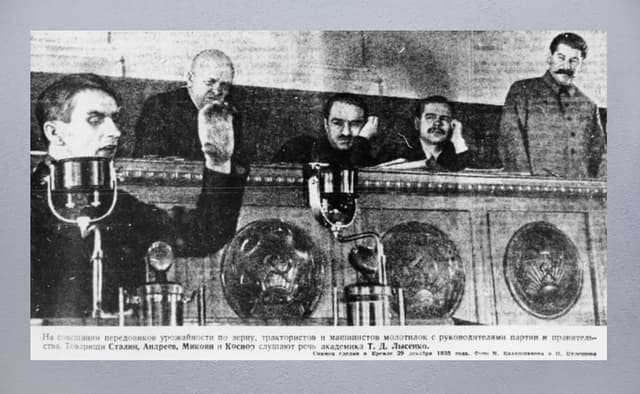

This tragic scandal was a strong blow to the Lamarckian school. It was in these circumstances that Trofim Lysenko rose to power in the Soviet Union, the USSR's own scientific hero of Neo-Lamarckian dialectical materialist biology.

Lysenko was an agronomist who despised genetics. He, the Lavrentiy Beria of agricultural science, wielded ideological dogma like a weapon, purging established Mendelian principles with the same ruthlessness Beria applied to human lives in the political domain. He and Beria ended up creating the most ruthless killing machine of Marxist Inquisition that targeted the geneticists.

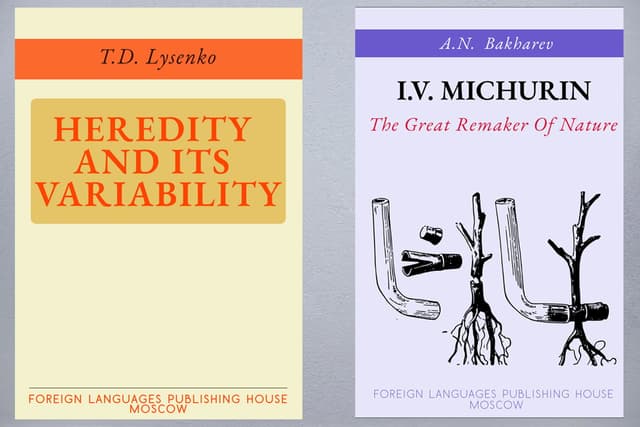

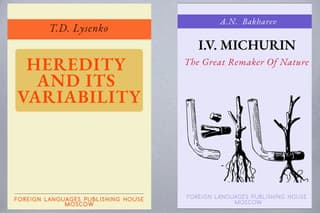

The experience of growing up during the Nehruvian era, with its abundant availability of Soviet popular science publications, provides a crucial lens through which to understand this tragedy. While these texts once provided ordinary Indian students with cost-effective, high-quality popular science books, they also serve today as a stark reminder of the insidious influence of state ideology on scientific discourse.

Examining Vavilov's fate alongside the rise of Lysenkoism offers a powerful inoculation against the dangers of ideological censorship, a practice that, in its extreme forms, can devolve into a modern-day inquisition. These Soviet books today offer a unique opportunity to witness the manipulation of science for political ends, solidifying the vital importance of safeguarding the integrity of scientific inquiry and understanding the historical consequences of its suppression.

They provide a tangible, historical lesson in the necessity of vigilance against any force that seeks to bend truth to its own agenda, a lesson that Vavilov's silenced voice continues to echo.

In his 1951 book, published by the Foreign Languages Publishing House in Moscow, Lysenko pitted his own theories against established genetics, which he dismissed as fundamentally flawed. He even redefined the purpose of genetics as a science in a bizarre way:

A study of the heredity (nature) of a given living body does not require the crossing of that plant or animal with one possessing another heredity. The real purpose of studying heredity is to detern1ine the relation of an organism of a given nature to its environmental conditions.T.D.Lysenko, Heredity and its Variability, Foreign Languages Publishing House, Moscow, 1951, p.7

He claimed cytogeneticists simply jotted down some things they saw in a microscope and imagined the rest. He wrote decisively:

The cytogeneticists proceed from the idea that heredity is a special substance different from the ordinary body and contained in the chromosomes of the cell nuclei.... Such a conception is absolutely unacceptable, especially to biologists.ibid., p.110

Mendelian laws, the very basis of genetics, were ridiculed as 'pea laws'. This dismissal was not an academic disagreement; it was a declaration of war on reason itself.

Lysenko's doctrine, which he wrapped in the banner of a horticulturalist named Ivan Michurin, was a politically engineered construct designed to serve the Stalinist state's philosophical framework. It posited a world where genetics did not exist, where the organism was infinitely malleable, and where traits acquired through environmental 'training' could be instantly inherited. This was a biology of pure will, a perfect mirror for a totalitarian regime that believed it could re-engineer not just society, but nature itself, through sheer force.

A 1954 biography, I.V. Michurin: The Great Remaker of Nature, leaves no ambiguity about the doctrine's political allegiance. It asks how Michurin became a pioneering scientist without guidance from prior biologists, and answers: "Michurin carefully studied the works of Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin and was guided by them in his activities. This enabled him to rise to a great height of scientific generalization." The book quotes Michurin himself asserting with dogmatic certainty:

Only on the basis of the teachings of Marx, EngeJs, Lenin, and Stalin ... can science be fully reconstructed.... The philosophy of dialectical materialism is an instrument for changing this objective world.A.N.Bakharev, ‘I.V. Michurin: The Great Remaker of Nature,Foreign Languages Publishing House, Moscow, 1954, p.8

This framing removes the evaluation of Michurin's work from the domain of empirical biology to that of ideological correctness. The biography buttresses this position by quoting Lenin's dictum that for a natural scientist to prevail against the 'onslaught of bourgeois ideas,' he must be a 'dialectical materialist'.

Vavilov was not the only eminent scientist who suffered under this Marxist Inquisition.

Another great scientist who suffered right from the reign of Lenin was Nikolai Koltsov (1872–1940). He was a strong opponent of Lysenko. He allegedly died because of a stroke. But recently it had come to light that he was poisoned by the secret police of the USSR (NKVD). Such suppression of scientific studies for the sake of ideological reason actually resulted in the loss of knowledge not just for the USSR but for the entire humanity.

In 1927, Koltsov had hypothesised that inherited characteristics are recorded in special double-stranded giant molecules. The double helical structure was not revealed until 1953, and that too was by the non-Russian West, a delay that carries a potent historical lesson.

In their zeal to defend the honour of a separate Russian science, its self-proclaimed patriots effectively forfeited the nation's chance to lead a profound scientific revolution. It serves as a powerful reminder about what constitutes genuine patriotism.

By this logic, any biologist who did not subscribe to dialectical materialism was an agent of a hostile worldview, and their scientific conclusions were inherently suspect. Genetics was labelled a 'reactionary, idealistic theory of heredity,' and its practitioners were branded 'academic cretins and reactionary bourgeois cosmopolitans' (p.67). This is a sample of how geneticists were considered enemies of the State.

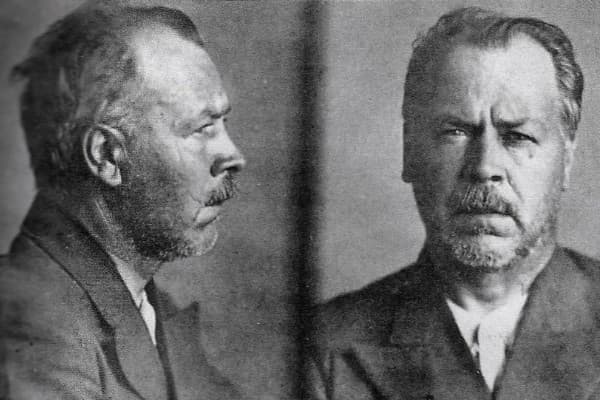

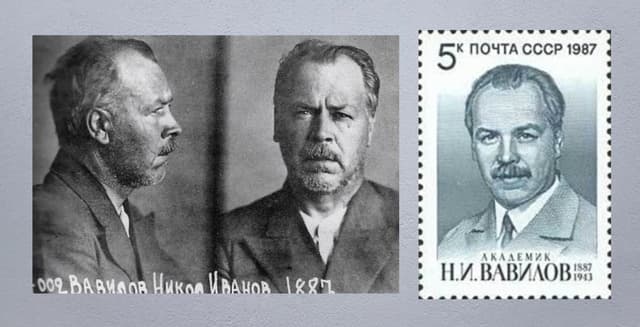

Nikolai Vavilov, then a world-renowned geneticist and director of the Lenin All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences, became Lysenko's most prominent target. Vavilov had amassed the world's largest collection of seeds, understanding that genetic diversity was the key to long-term crop improvement. He recognised Lysenko's theories as baseless pseudoscience and publicly voiced his disagreement.

For this crime of scientific integrity, he was targeted. In 1940, while on a collecting expedition, Vavilov was arrested by the secret police. He was accused of absurdities, including being a British spy and 'fighting against the theory and the [practical] works of Lysenko and Michurin'. After brutal interrogations, he was sentenced to death, a sentence later commuted to twenty years in the Gulag.

In 1943, after three years of horrible suffering in prison, Nikolai Vavilov, the man who dreamed of ending world hunger, died of starvation in a Saratov prison.

If the purges of geneticists, crowned by the arrest and death of Vavilov, were the means of victory for 'Marxist biology,' then the famines of Ukraine were its ultimate and most tragic falsification. A scientific theory is ultimately judged by its predictive power and its ability to produce results. Lysenkoism, born from a promise to solve the Soviet Union's agricultural crisis, was put to the test on a continental scale. It promised revolutionary yields and an era of unprecedented abundance. It delivered mass starvation.

Vavilov was 'rehabilitated' by the Soviet regime decades after his death.

In 1971, a popular science book on genetics was published in Russian. It was translated and published in 1978. There was not a single word about Lysenko. Michurin was mentioned just twice in passing with a half-truth claim that he took a great interest in mutation studies. That he was a rhetorical negationist with respect to the reality of genes is not mentioned. But Vavilov was now portrayed in glowing terms:

Of singular importance for selection are the works of Nikolai Vavilov. In the early twenties he formulated the 'law of homologous lines'.... Guided by this law one can confidently search for what it is possible to find and avoid futile efforts.... Vavilov did something unprecedented. He travelled all over the world in search of relatives of our cultivated plants. He discovered the centres from where cultivated plants originated and collected an immense treasure of material for further selection work. ... In 1942 Vavilov died. ... Several years ago when Heredity, the international journal of genetics, was founded in Great Britain, its modest red cover was framed with the names of the scientists who had made the greatest contribution to genetics, about a dozen names in all. Among them, along with that of Darwin, was Vavilov's.N.Luchnik, 'Why I'm like Dad', Mir Publishers, Moscow, 1971:'78, pp.116-7

In 1979, official Soviet press published a justified hagiography of the scientist in Russian. It would be translated and published in English only in 1987. However, there is not a single mention of his arrest under Stalin. Instead, a three-day arrest during the pre-revolutionary days by the Russian regime then was described in an eloquent and emotional passage. Even the year of his death was not mentioned. His death was alluded to but not written directly. Such was the falsification of history that continued in the Soviet regime even decades after Stalin.

The story of Vavilov and Lysenko is more than a historical tragedy; it is a timeless cautionary tale.

It demonstrates with chilling clarity the catastrophic consequences that unfold when any society, whether guided by political ideology or religious dogma, places its beliefs before verifiable truth. The path that led to the famines of the Soviet Union was paved with the suppression of evidence, the persecution of dissent, and the elevation of political loyalty over scientific fact.

From this dark chapter of history, the world must take a vital lesson, a lesson enshrined in the words of Swami Vivekananda thus:

Truth does not pay homage to any society, ancient or modern. Society has to pay homage to Truth or die. Societies should be moulded upon truth, and truth has not to adjust itself to society.The Real Nature of Man, 1896

In Cosmos: Possible Worlds, the modern successor to Carl Sagan's iconic series, host Neil deGrasse Tyson dedicates an episode to the life and achievements of Nikolai Vavilov. The story charts his profound scientific contributions and his tragic yet triumphant death, culminating in Tyson reading a line from one of Vavilov's love letters:

I do not hesitate to give my life even for the smallest bit of science.

That was a vow he would ultimately fulfil.

The sacred memory of Nikolai Vavilov should be a beacon, celebrated internationally not just as a monument to a great scientist, but as a day of an individual who belongs to all humanity, standing for pursuit of truth and the welfare of all humanity against the forces of ideological indoctrination and tyrannical power.

Vavilov died on this day, 26 January, in 1943. Let us remember this great soul of our species who could have given us a blueprint for survival during the great challenges that the deep future might bring us.