Technology

How To Think About India's Place In The AI Race

Raghavan S Rao

Jan 24, 2026, 06:00 AM | Updated Jan 25, 2026, 10:54 AM IST

At the World Economic Forum in Davos on January 20, 2026, Union Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw found himself in a position familiar to any Indian representative at global forums: being talked down to.

When IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva casually placed India in a "second tier" of AI nations—behind America and China, lumped with capable but lesser powers—Vaishnaw pushed back with vigour.

"India is clearly in the first group," he insisted, citing the Stanford AI Index: third globally in AI vibrancy, second in talent concentration. The country, he argued, was already "the largest supplier of AI services" and building systematically across five foundational layers: applications, models, chips, infrastructure, and energy.

Vaishnaw was doing his job, and doing it well. It would have been absurd for India's Minister of Electronics and IT to sit on a Davos stage and enumerate his country's capability gaps for an international audience.

At global forums, you project strength, claim your place at the table, and let the rankings speak. His citations were accurate; his framing was strategic; his confidence was appropriate. When the IMF Managing Director casually diminishes your country's standing, you push back. This is what ministers do, and Vaishnaw did it effectively.

But what serves India well at Davos does not serve Indians well at home. The risk is that ministerial confidence curdles into national complacency—that we mistake projecting strength for possessing it, that we confuse a good performance with a won race.

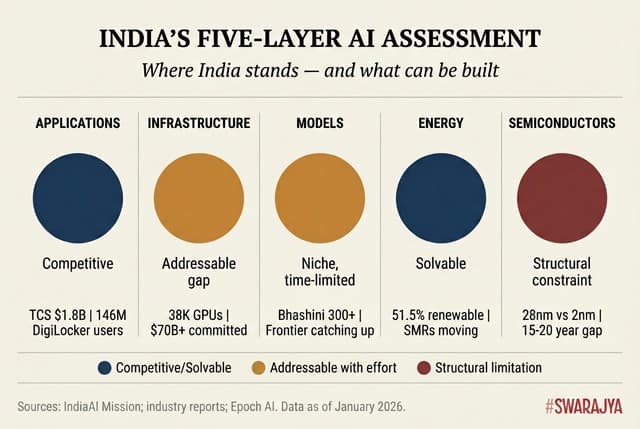

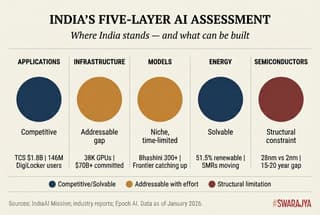

Vaishnaw's five-layer framework is genuinely useful for understanding India's AI position. Examining each layer honestly, however, reveals a more complex picture than triumphalism allows.

The ₹10,372 crore ($1.25 billion) IndiaAI Mission represents serious intent; it also represents roughly what OpenAI or Anthropic burns through in six months.

Understanding where India actually stands—and what must be built—requires examining each layer against global benchmarks, with the honesty that Davos does not permit but domestic strategy demands.

Layer 1: Applications — India's Genuine Strength, Within Limits

India's claim to AI applications leadership deserves serious examination. The country's IT services industry—TCS, Infosys, Wipro, HCL—has genuinely pivoted toward AI, with TCS reporting $1.8 billion in annualized AI revenue and 76% of its recent deals involving AI components. This is real progress, built on decades of services industry expertise.

But context matters. Accenture alone booked $3.6 billion in generative AI consulting revenue in 2024, while Boston Consulting Group generated $2.7 billion from AI services—20% of its total revenue from a capability that barely existed two years prior. IBM has built a $6 billion AI book of business since launching Watsonx.

The global AI consulting market, valued at $16.4 billion in 2024, is led by Tier 1 vendors (Accenture, IBM, Deloitte, PwC, Capgemini) who command 50-55% market share. Indian firms occupy Tier 2—capable and growing at 15-20% share, but not yet price-setters or capability-definers.

Where India genuinely excels is in domestic deployment. UPI processes 18 billion transactions monthly with AI-powered fraud detection. DigiLocker serves 146 million users with AI-enhanced verification. The PM-KISAN AI chatbot reaches 110 million beneficiaries through Bhashini's multilingual support.

In banking, HDFC's Eva handles 6.5 million queries with 85% accuracy and sub-200ms fraud scoring; SBI's SIA can process 864 million queries daily; ICICI's iPal manages over 6 million queries at 90% accuracy. In healthcare, eSanjeevani has facilitated 318 million telemedicine consultations. These are not pilot projects—they are production systems operating at scales that European nations cannot match. India's capacity to deploy AI at population scale is genuine and globally distinctive.

The structural question is whether India can move from services delivery to services definition. When global enterprises need help deploying frontier models, they typically turn first to firms with deeper model partnerships and proprietary tooling. Indian firms execute implementations; Western firms increasingly define architectures.

India has a genuine competitive position—strong but not dominant—with particular strength in population-scale deployment. The claim to being "the world's largest supplier of AI services" is aspirational. The work is to make it descriptive.

Layer 2: Models — A Niche Strategy Racing Against Time

The gap between India's indigenous LLM models and the global frontier is not merely large; it is also structural.

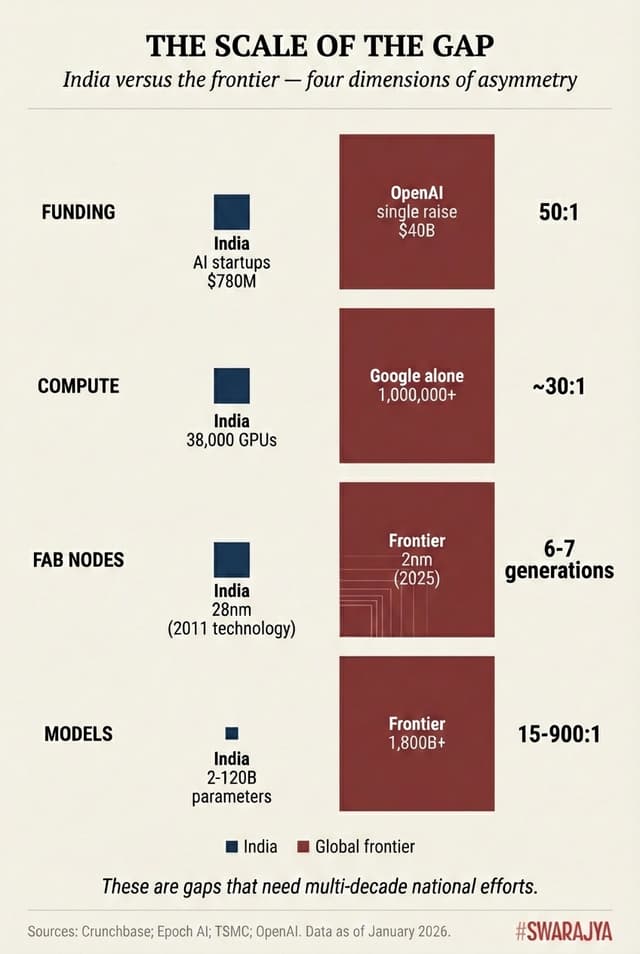

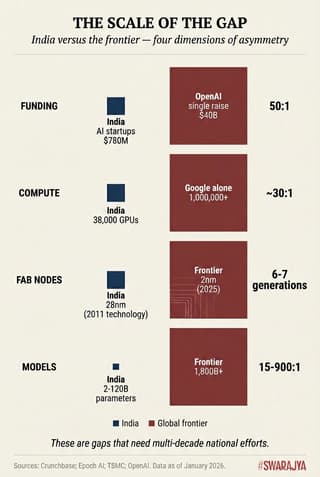

Sarvam AI's flagship model operates at 2 billion parameters; even its ambitious sovereign LLM—funded with ₹98.68 crore and 4,096 H100 GPUs—targets 70-120 billion parameters. The frontier has moved far beyond: over 30 models have now been trained at the 10²⁵ FLOP scale that characterised GPT-4. Frontier models routinely exceed 1 trillion parameters.

The economics are also unforgiving. OpenAI raised $40 billion in March 2025 alone, reaching a $300 billion valuation. Anthropic's $13 billion Series F valued it at $183 billion. These companies project revenues of $12.7 billion (OpenAI) and $9 billion (Anthropic) for 2025. India's entire AI startup ecosystem raised $780 million in 2024. The funding asymmetry is roughly 50:1.

Yet India's model strategy may be more coherent than raw parameter counts suggest. The country has consciously chosen "niche but sovereign"—models optimised for India's 22 scheduled languages rather than competing on English-language benchmarks.

Less than 1% of global AI training data is Indian; multilingual capability requires purpose-built solutions. Bhashini's 300+ models covering Indian languages address a genuine gap. Tech Mahindra's Project Indus targets Hindi and 37 dialects at a fraction of frontier costs.

The ecosystem extends beyond government initiatives. AI4Bharat at IIT Madras has contributed IndicTrans2—a 1.1 billion parameter translation model covering all 22 scheduled languages—and IndicBERT to the global research community.

The IIT consortium's Hanooman project offers models from 1.5 to 40 billion parameters across Indian languages. BharatGen, funded by DST at ₹235 crore and targeting July 2026 completion, aims to become the world's first government-funded multimodal foundation model.

Sarvam's sovereign LLM project, backed by 4,096 H100 GPUs, represents a serious bet that India can build models at meaningful scale. These are real efforts with real teams—not vapourware.

The question is whether this niche can survive. GPT-4 and Claude already perform respectably on Indian languages; each model generation narrows the gap that justified sovereign alternatives. Google's Gemini 3 Pro boasts a 1 million token context window. DeepSeek delivers frontier-class performance at 10-30x lower cost. India's linguistic niche faces pressure from both American capability and Chinese pricing.

The linguistic-sovereignty strategy makes sense given constraints. But the niche is shrinking. Perhaps there is also some credit in what some Chinese companies have done: develop innovative means to make LLMs with lesser compute resources.

Layer 3: Semiconductors — The Gap That Cannot Be Closed

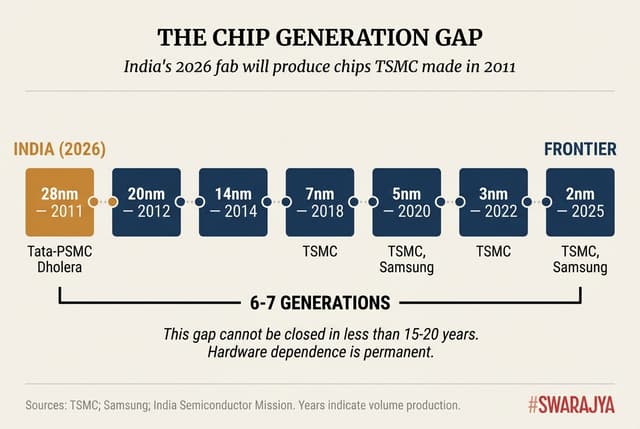

The semiconductor layer requires the most unflinching assessment because the gap is structural, generational, and not closable on a fast timeline.

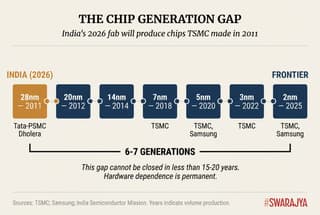

India's flagship fab project—Tata-PSMC at Dholera—will produce chips at 28nm-110nm nodes when it begins operations in late 2026. TSMC introduced 28nm in 2011. Further it is a fab that will license tech from PSMC and is not necessarily a fab made with technology/tech know how obtained from India. This is a distance India has only now begun to march.

Meanwhile the global frontier has moved to 2nm, with TSMC achieving mass production in Q4 2025. This represents 6-7 technology generations of separation—a gap that cannot be meaningfully reduced in less than 15-20 years.

TSMC targets 100,000 wafers monthly at 2nm by 2026; its total capacity approaches 1.3 million wafers monthly. Tata-PSMC targets 50,000 wafers at mature nodes—roughly 4% of TSMC's capacity in a segment representing only a fraction of semiconductor value.

Also it's not just about fabs.

Semiconductor manufacturing requires hundreds of specialty inputs where India has near-zero domestic production: high-purity acids (sulfuric, nitric, hydrochloric), over 30 specialty gases (the Ukraine conflict disrupted 50% of global neon supply), sub-65nm photoresists, and silicon wafers. ASML's EUV lithography machines—essential for any node below 7nm—cost $350+ million each, are export-controlled, and have order books allocated to TSMC, Samsung, and Intel through the late 2020s. India has no pathway to acquiring them.

Consider the full supply chain for an AI chip like NVIDIA's H100: designed in America using EDA tools from Cadence and Synopsys, manufactured at TSMC's 4nm node in Taiwan, assembled with advanced CoWoS packaging, incorporating high-bandwidth memory from SK Hynix in South Korea. India participates in none of these steps. The claim that the India Semiconductor Mission will create "self-reliance" confuses presence in the industry with capability at the frontier.

But let's also be real. India's strategic response has been sensible within constraints: focus on assembly, test, and packaging (OSAT). Micron's $2.75 billion ATMP facility, Kaynes Technology's OSAT plant, and the CG Power-Renesas joint venture represent legitimate participation without the fantasy of near-term frontier manufacturing. C-DAC's SHAKTI RISC-V processors demonstrate design capability—but manufacturing remains abroad.

The verdict on this layer is therefore that India can build meaningful presence in mature nodes and packaging. It cannot produce the advanced chips that define AI capability—not in five years, likely not in fifteen. This is the structural constraint that must be managed, not wished away. Hardware dependence seems permanent today and we must take measures to catch up.

Layer 4: Infrastructure — The Most Addressable Gap

The infrastructure layer shows India's most dramatic recent progress. The 38,000 GPU deployment under IndiaAI Mission exceeded the 10,000-unit target threefold. Subsidised access at ₹65/hour ($0.78)—versus $2.50-3.00 globally—does democratise compute for startups and researchers.

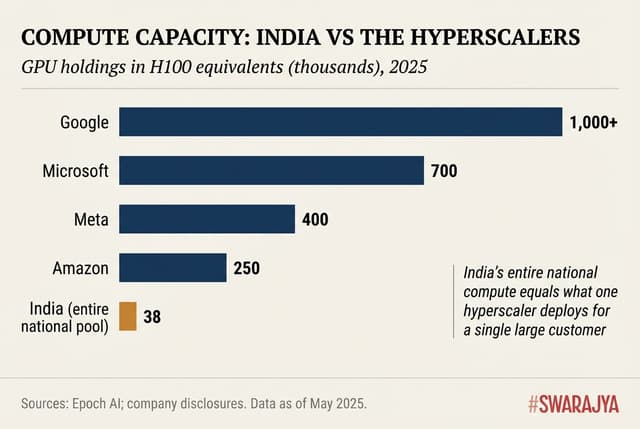

But the global benchmark is rather humbling. The United States hosts approximately 75% of global GPU cluster performance; China holds 15%. Google alone possesses the equivalent of over 1 million H100 GPUs. Microsoft holds roughly 700,000; Meta has 400,000; Amazon 250,000. India's entire national compute pool equals what a single hyperscaler deploys for one large customer.

The scale asymmetry becomes starker against frontier requirements. Training a GPT-4-class model required roughly 10²⁵ FLOP; leading labs now run jobs at 10²⁶ FLOP. xAI's Colossus cluster operates 230,000 GPUs with plans for 2 million. India's 38,000 GPUs represent perhaps 0.1% of frontier compute capacity.

India's approximately 1.5 GW of data centre capacity is projected to reach 8-9 GW by 2030. But hyperscalers are spending $380+ billion on AI infrastructure in 2025 alone. Reliance's proposed 3 GW Jamnagar facility would be transformative—but remains in planning while American hyperscalers already operate at gigawatt scale.

Yet infrastructure is the most addressable gap. Unlike semiconductor fabs requiring decades of capability building, data centres can be deployed in 2-3 years with sufficient capital.

The commitments are real: Google has pledged $15 billion for Indian infrastructure; Microsoft has committed $17.5 billion. Domestically, Yotta has partnered with NVIDIA for 32,768 GPUs across its Navi Mumbai and Greater Noida campuses; Jio plans to deploy NVIDIA GH200 Grace Hopper superchips at Jamnagar. The IndiaAI Mission's empanelment now includes 14 providers offering subsidised access to H100s, H200s, AMD MI300X, and Google Trillium TPUs. Capital is flowing; the question is execution speed.

The verdict: India has shown it can scale compute when prioritised. The gap remains enormous—100-1000x versus leaders—but this is the layer where capital can most directly purchase progress. The work is to convert announcements into operating capacity.

Layer 5: Energy — A Manageable Constraint

Energy emerges as India's most manageable challenge. India's 262.74 GW renewable capacity represents 51.5% of total installed power—a higher share than most major economies.

Indian data centres achieve Power Usage Effectiveness ratios of 1.4-1.6 versus 1.1-1.3 for global leaders—40-60% overhead versus 10-30%. Grid reliability issues force diesel backup, adding 15-25% to effective power costs.

Policy responses are well-designed. Data centres secured Infrastructure Status in 2022. States offer substantial incentives—Maharashtra provides ₹1/unit subsidies; Karnataka waives charges for facilities using 50%+ renewable power. The December 2025 SHANTI Bill allowing private nuclear ownership—a first in Indian history—opens a new pathway.

Adani-NPCIL discussions for 1.6 GW of small modular reactors in Uttar Pradesh are underway; six major industrial groups (Reliance, Tata, Adani, Hindalco, JSW, Jindal) have submitted proposals for 16 sites across six states. Nuclear provides the reliable baseload that AI workloads require—consistent output regardless of weather. Reliance's integrated approach at Jamnagar—co-locating a 3 GW data centre with dedicated solar and 30 GWh battery storage—represents the frontier solution.

Energy constraints are therefore just conventional infrastructure problems with identified solutions. This will not be what limits India.

What This Means: The Honest Assessment

How should Indians think about their country's AI position?

The answer is neither triumphalism nor defeatism but with honest gap analysis. Ashwini Vaishnaw was doing his job (and he did it well) of projecting India well.

By talent, India's position is genuinely strong—second globally in concentration, highest AI skill penetration rate worldwide. By application deployment, India competes credibly; 145 million DigiLocker users and 1.3 billion CoWIN vaccinations represent scale few nations can match.

By compute, the gap is severe but addressable with capital. By models, the niche is defensible but shrinking. By hardware, there is no near-term pathway to independence.

Comparing to peer nations provides context. The UK attracted $4.5 billion in AI funding in 2024—6x India's total. France's Mistral raised €1 billion in a single round. Japan has committed ¥10 trillion to AI and semiconductors. Korea's K-CHIPS Act provides $735 billion. On the Tortoise Global AI Index, India ranks 10th—leading emerging markets but behind developed-nation peers with smaller populations.

The structural difference matters, and Indians should understand this clearly. UK and French AI strength rests on research depth and startup innovation—DeepMind invented transformers; Mistral built a frontier model from scratch in eighteen months. This is capability that creates new possibilities. Japanese and Korean strength rests on hardware manufacturing—the fabs, the memory chips, the display panels that AI systems require. This is capability that captures value from every AI deployment worldwide.

Indian strength rests on talent availability and services delivery—the engineers who implement, deploy, and maintain AI systems for global clients. This is valuable, but it is downstream capability.

Services can be contracted; frontier research and hardware manufacturing create the options that services then execute. India excels at the application layer precisely because it depends on others for the foundational layers beneath.

The five-layer framework, when examined honestly therefore yields a clear picture. India has two layers of competitive strength: applications, where decades of services expertise translate into genuine capability, and infrastructure, where capital can purchase rapid progress.

One layer reflects a coherent but time-limited strategy: sovereign models serving Indian languages remain useful today but face erosion as frontier systems improve.

One layer is a solvable problem: energy constraints yield to conventional policy and investment.

And one layer represents a structural constraint that no amount of effort will overcome on relevant timelines: semiconductor dependence is permanent.

This is not a story of failure. India ranks first globally in AI skill penetration, deploys AI at population scales few nations can match, and has tripled its compute targets in a single year. But nor is it the triumph that celebratory headlines suggest. The 50:1 funding gap with frontier labs, the 6-7 generation gap in chip manufacturing, the 100-1000x gap in compute capacity—these are not problems that vanish with confident assertions.

What India can build in a decade is globally competitive AI services, population-scale applications, regionally-leading infrastructure, useful sovereign models, and meaningful presence in mature semiconductor nodes.

What it cannot achieve in a decade are hardware independence, frontier model capability, or compute parity with US-China leaders. (I'd love to be proven wrong!)

The honest response is neither pride nor despair—it is pride and work. We can celebrate the 38,000 GPUs while noting they represent 0.1% of frontier capacity. We can value Bhashini's 300 models while preparing for GPT-5's multilingual capabilities. Clear-eyed assessment is not defeatism; it is the precondition for effective strategy.

Vaishnaw's Davos speech served its purpose. Now comes the harder part: building what can be built, managing what cannot be changed, and maintaining the honesty to know the difference.

A public policy consultant and student of economics.